Donald D. Harrison, PhD, DC, MSE Deed E. Harrison, DC

INTRODUCTION

In December 1980, Chiropractic BioPhysics® or CBP® Technique, was originally named by Drs. Donald Harrison, Deanne Harrison, and Daniel Murphy for “physics applied to biology in chiropractic”. Since that time, Drs. Donald and Deed Harrison, (along with a number of other contributors) have authored Seven CBP Texts Books and published more than 130 scientific studies investigating different aspects of CBP.1-7 Thus, today, CBP Technique is one of the foremost investigated techniques in Chiropractic and both Dr. Don and Dr. Deed are among the leaders in the profession’s researchers.

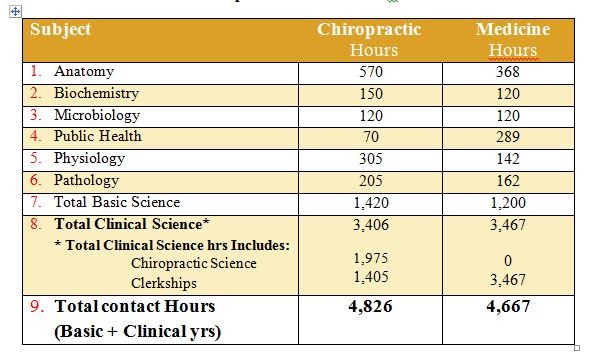

Table 1.

CBP Technique Scientific Publications. These publications detail different aspects of the technique procedures, protocols, and outcomes.

CBP Goals of Care

CBP Technique emphasizes optimal posture and spinal alignment as the primary goals of chiropractic care while simultaneously documenting improvements in pain and functional based outcomes (See Figure 1). The uniqueness of CBP treatment is in structural rehabilitation of the spine and posture. In general the goals of CBP Care are:

-

Normal Front & Side View Posture

- Center of mass of head, rib cage & pelvis vertically aligned in Front and Side views.

-

Normal Spinal Alignment

- Front view: vertical alignment

- Side View: Harrison Ideal or Average Spinal Model

- Normal function

a. Improved Range of Motion and quality of movement,

b. Improved muscle strength,

-

Improved Health & Symptom Improvements

- Neck disability index,

- Oswestry low back index,

- SF 36 or Health Status Questionaire

Ideal Postural Alignment

Figure 1. Ideal postural alignment is depicted in both the frontal and side views. In each view, the center of mass of the skull, thorax, and pelvis are in a vertical line with respect to gravity. In the frontal view, the spinal column is vertically aligned-a straight column- with respect to gravity. In the side view, the spine has three primary curvatures which will be described below:

- Neck Curve---Cervical Lordosis,

- Ribcage Curve---Thoracic Kyphosis,

- Low back Curve---Lumbar Lordosis

©CBP Seminars & Deed E. Harrison, LLC.

Ideal Spinal Alignment: Harrison Full Spine Model

As in all fields of study dealing with the human body, i.e. physiology, hematology, anatomy, etc., there exist normal values for alignment of the spine. The Harrison Spinal Model is an evidenced based model for side view spinal alignment. It is the geometric path of the posterior longitudinal ligament or the backs of the vertebra from the 1st neck vertebra to the bottom of the lower back or top of the sacrum. See Figures 2-6 below detailing the Harrison Spinal Model

CBP researchers have extensively published ideal and average models for the human spinal curvatures as viewed from the side. This research has lead to the finding of the ‘Harrison Spinal Model’. This model details both Ideal and Average geometric shapes for the curves of the spine from the side. Additionally, ideal and average ranges for the spinal segmental angles for each of the spinal regions have been identified. The neck or cervical spine should have a geometric shape that approximates a ‘piece of a circle’. The ribcage or thoracic spine should have a geometric shape that approximates an oval-elliptical shape. And the low back or lumbar spine should have a geometric shape that approximates an oval-elliptical shape.26-31

These are “evidence based” models. In fact, the CBP neck-cervical circular model27 and the low back- lumbar elliptical model29 have both been found to have discriminative validity between pain and non pain subjects. In other words, the Harrison Spinal Model has been found to be able identify pain subjects versus non-pain subjects by what their spinal x-ray shapes are.

Figure 3. The three figures above demonstrate the concept that each spinal region has a normal ‘geometry’ or shape of the spinal curves. On the readers left is the Neck or Cervical spine-Here the shape in the neck curve should approximate a piece of a circle. In the Center is the Ribcage or Thoracic spine—Here the shape in the ribcage should approximate a piece of an oval or ellipse. On the Right is the Low back or Lumbar spine—Here the shape in the low back should approximate a piece of an oval or ellipse. ©CBP Seminars & Deed E. Harrison, LLC.

Figure 4. The Harrison Full Spine Model. On the readers left is the exact geometric model of the side view of the spinal curves as identified by Harrison and colleagues. This model can be used to determine what is wrong-abnormal with a given patient’s side view of the spine. For example, a full spine x-ray on the right is shown. The red-curved line represents the Harrison spinal model and this shows where the patient’s spinal vertebra should be lined up. It is apparent that this patient has altered spinal alignment as they do not fit even close to the Harrison Idealized Spinal Model.

©CBP Seminars & Deed E. Harrison, LLC.

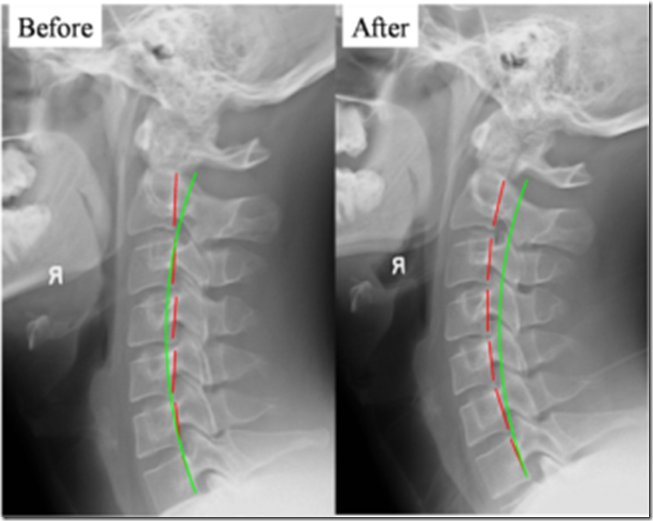

Figure 5. The Harrison Spinal Model in the Neck-Cervical region. The Harrison spinal model is depicted as theGREEN curved line in this figure. On the Right is a normal curved patient x-ray. On the Left is an abnormal curved patient x-ray; where the patient’s abnormal shape is shown by the Red dashed line. The Harrison Spinal Model in the neck has been shown to reasonably predict which person will have neck pain compared to normal subjects. ©CBP Seminars & Deed E. Harrison, LLC.

Figure 6. The Harrison Spinal Model in the Low back or Lumbar region. The Harrison spinal model is depicted as the RED curved line in this figure. On the Right is a normal curved patient x-ray. On the Left is an abnormal curved patient x-ray; where the patient’s abnormal shape is shown by the faint dashed line. The Harrison Spinal Model in the low back has been shown to reasonably predict which person will have low back pain compared to normal subjects. ©CBP Seminars & Deed E. Harrison, LLC. ©CBP Seminars & Deed E. Harrison, LLC.

X-Ray Analysis and Utilization

To establish optimal and average sagittal models, x-ray analysis and line drawing procedures are utilized. CBP protocols require that the doctor must measure the displacements on spinal radiographs (segmental Subluxation). Both lateral-side view and anterior to posterior (AP) or frontal view CBP x-ray line drawing procedures have been studied and found to be reliable.32-36 Furthermore, CBP utilizes standardized x-ray positioning procedures that have been studied and found to be reliable.36

As with measures of pain intensity, range of motion, and quality of life, periodic assessment of spinal structural alignment is important to evaluate progress and determine when maximum patient improvement has been reached. In CBP Technique, the use of initial and follow-up spinal x-rays or radiographs is deemed necessary; however, some in chiropractic have condemned the use of follow-radiographs to collect alignment data.37-39Importantly, there is data to show that the use of medical/chiropractic x-rays constitutes a very minor health risk and in fact has been shown to be of benefit (decreased sickness and cancer mortality rates) in some studies.40-42

In reality, the only way to see what an individual patient’s spine alignment looks likes, is to obtain spinal imaging such as Radiography or X-ray. No-one would not take their car to the mechanic and say: “Something’s wrong with my engine but don’t look under the hood”--Would you? Then why would anyone want a Chiropractor to adjust-treat their spine without having an x-ray to see what the person’s spine looked like?—Would You?

CBP Postural Analysis

Previously, engineering concepts were used to describe all spinal-vertebral segmental movements as rotations and translations in 3-dimensions.10 However, Dr. Don Harrison was the first to describe abnormal postures of the head, rib cage, and pelvis in this manner.1-3,9 Figures 7 and 8 depict the twelve simple motions in six-degrees of freedom as rotations and translations of the human head, ribcage, and pelvis:

· Rotation is a turning, twisting, or tilting movement and is an ‘angular’ movement,

· Translation is a straight line movement (up, down, left, right, forward, backward)/

Figure 7. The possible translation postures (Tx, Ty, Tz) of the head, rib cage, and pelvis are depicted in 3-dimensions. In 1980, Dr. Don Harrison termed these pairs on any one axis as Mirror Images®. Whichever Abnormal postures were found to exist in the patient, these postures would be placed into their Mirror Image® before a force was applied with an adjusting instrument, drop table, exercise and/or traction. ©CBP Seminars & Deed E. Harrison, LLC

Figure 8. The possible postural rotations (Rx, Ry, Rz) of the head rib cage and pelvis are depicted in 3-dimenesions. In 1980, Dr. Don Harrison termed these pairs on any one axis as Mirror Images®. Whichever postures were found to exist in the patient, these postures would be placed into their Mirror Image® before a force was applied with an adjusting instrument, drop table, exercise and/or traction. ©CBP Seminars & Deed Harrison, LLC.

The postural and spinal displacements are the determining factors for deriving a patient’s individualized program of care. Prior to performing CBP Mirror Image® postural set-ups, the patient’s initial presenting abnormal posture(s) must be exactly determined. Ideal posture can be precisely described as vertical alignment of the centers of mass of the head, ribcage, and pelvis with respect to gravity (Figure 1 above). In other words, none of the rotations and translations in Figures 7 and 8 can be present. Using this definition, abnormal postural rotations and translations can be determined.

Mirror Image® Postural Adjustments

In March 1980, Dr. Don Harrison originated postural Chiropractic adjusting procedures that he coined “Mirror Image®”. Clinically, these adjusting set-ups were found to result in postural and spinal alignment improvements verified with follow up x-ray; this impression would be subjected to studies later as shown in Table 1 above.

For each of these postures illustrated in Figures 7 and 8, Dr. Don Harrison and his brother Glenn Harrison originated drop table adjustments, instrument adjustments (both table and hand-held). For these new Mirror Image® patient positions, Dr. Don Harrison placed the patient in their opposite posture. These Harrison Mirror Image® positions can be described as “reflecting” the patient’s head, rib cage, and/or pelvis across the median-sagittal plane in the AP view, and positioning the head, rib cage, and/or pelvis across the mid-frontal plane in the lateral view.9 Figures 9 and 10 demonstrate two examples (there are literally thousands more as there can be many postural combinations of each region) of Mirror Image® Adjustments utilized in CBP Technique.

Mirror Image Adjustments, assists the Chiropractor in the rehabilitation of the patient’s posture. In theory, these adjustments ‘re-balance’ the bodies sense of proper balance or alignment by way of triggering improved muscle and nerve reflexes. Thus, postural adjustments as performed with drop table, hand-held instrument, or evenmirror imageÒ manipulation procedures, are performed for resetting the nervous system regulation of postural muscle balance.51

Figure 9. Mirror Image adjustment example for the head posture. The patient has forward head posture (translation) and the skeletal animation shows what happens to the spine with this posture. On the right is the CBP Mirror Image adjustment. The posture is placed in its opposite position and then a Chiropractic adjustment is performed. ©CBP Seminars & Deed E. Harrison, LLC.

Figure 10. Mirror Image adjustment example for the ribcage posture. The patient has right lateral ribcage posture (translation) and the skeletal animation shows what happens to the spine with this posture. On the right is the CBP Mirror Image adjustment. The posture is placed in its opposite position and then a Chiropractic adjustment is performed. ©CBP Seminars & Deed E. Harrison, LLC.

Mirror Image® Postural Exercises

Further, in 1980-1986, Dr. Don and Dr. Glenn Harrison began developing and testing Mirror Image® posture exercises.1-3 Mirror imageÒ exercises are performed to stretch shortened muscles and to strengthen those muscles that have weakened in areas where postural muscles have adapted to asymmetric abnormal postures. Although strength and conditioning exercise has not proven to correct posture,46 postural exercises performed in the mirror imageÒ have shown initial promise in the reduction of posture and spinal displacements.47-50Figures 11 and 12 demonstrate Corrective Mirror Image exercises for the same postures as in Figures 10-11.

Figure 11. Mirror Image exercise example for the abnormal forward head posture. The patient has an abnormal forward head (translation) posture and the skeletal animation shows what happens to the spine with this posture. On the right is two different CBP Mirror Image exercises—one with just the patient’s muscles and body as resistance and the other with an elastic band for increased contraction effort. The patient actively maneuvers their posture into the opposite or Mirror Image position. ©CBP Seminars & Deed E. Harrison, LLC.

Figure 12. Mirror Image exercise example for an abnormal lateral shifted (translated) ribcage posture. The patient has right lateral ribcage posture (translation) and the skeletal animation shows what happens to the spine with this posture. On the right is two different CBP Mirror Image exercises—one with just the patient’s muscles and body as resistance and the other with an elastic band for increased contraction effort. The patient actively maneuvers their posture into the opposite or Mirror Image position. ©CBP Seminars & Deed E. Harrison, LLC.

Mirror Image® Postural and Spinal Traction

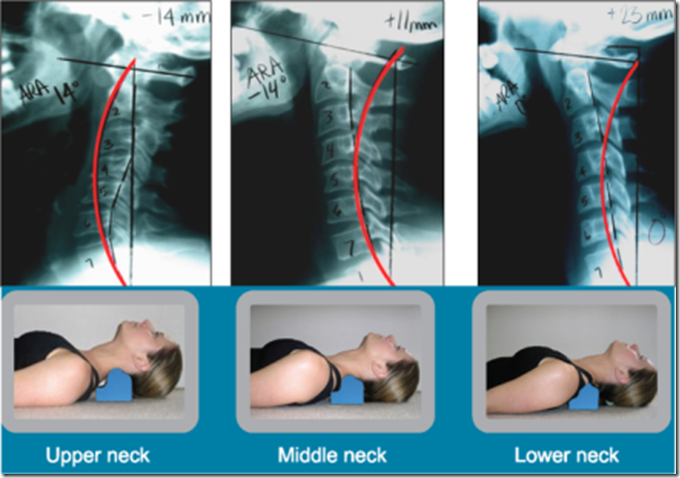

Additionally from 1980-1986, for use in difficult cases, Dr. Don Harrison and Dr. Glenn Harrison originated several Mirror Image® postural traction (rotations and translations of the head, rib cage, and pelvis) and cervical extension (backwards bending) traction methods to restore the sagittal cervical curve. These CBP Technique cervical extension traction methods were improved upon over the years by several other CBP practitioners.

From 1996-2000, several postural and spinal traction methods to restore thoracic and lumbar sagittal curvatures were developed by Dr. Deed Harrison; Dr. Don Harrison’s son.11-13 Dr. Deed began to further refine the CBP Technique cervical traction methods with an analysis of head posture, curve configuration, thoracic curvature, gender, and body size.4 From 1992-2004, six non-randomized clinical control trials,13-18 one randomized clinical control trial,19 and five case studies20-24 have been performed on these CBP Technique Mirror Image®procedures.

Postural mirror imageÒ and extension traction for the side view spinal curves provides sustained loading periods of 10-20 minutes and is necessary to cause visco-elastic deformation to the resting length of the spinal ligaments, muscles, and discs.52 In clinical controlled trials, extension traction, as done in CBP Technique, is the only proven method (without surgery) shown to consistently correct abnormal spinal curvatures back towards their normal alignment.

There are MANY types of spinal extension traction methods used in CBP Technique; some are more aggressive and technical than others. Whereas some forms of spinal extension traction are available for patients to use at home; the examples shown in Figures 13-14 are in office types only. Note: Each patient’s spine is unique and thus, a variety of traction devices are used depending upon the exact condition of the patient.

Figure 13. Three different subluxations (abnormal alignment) of the cervical curve and their respective Mirror ImageÒ traction methods. In A, hypolordosis with mild anterior head translation requires compression extension traction in B. In C, slight kyphosis with posterior head translation requires 2-way non-compression traction in D. In E, reversal of the upper cervical curve with mild anterior head translation requires compression extension 2-way traction in F.4,14-16 ©CBP Seminars & Deed E. Harrison, LLC.

Figure 14. Two different subluxations of the lumbar curve and one of the thoracic curve and their respectiveMirror ImageÒ traction methods. In A, lumbar kyphosis with anterior thoracic translation requires 3-point bending extension traction in B (shown standing). In C, slight lumbar kyphosis with posterior thoracic translation requires 3-point bending in D (shown supine). In E, hyper-kyphosis of the thoracic curve requires 3-point bending thoracic traction in F (shown standing). ©CBP Seminars & Deed E. Harrison, LLC.

CBP Protocol of Patient Care

Treatment Interventions

The CBP protocol of care recommends that relief care (traditional chiropractic management) be separated from structural rehabilitation of the spine and posture. In this regard, the typical patient would receive an initial 3 weeks of care (4 times per week or 12 visits) aimed at improving segmental and overall spinal range of motion (RoM) and pain intensity/frequency. Treatment interventions/methods would consist of any number of segmental adjusting techniques the chiropractor prefers to utilize (Diversified, Gonstead, Activator, etc…).

After, the initial relief care examination (average 12 visits), CBP structural rehabilitation procedures would begin and include Mirror Image® exercises, adjustments, and traction (referred to as the E.A.T protocol). The mirror image® posture positions are the rotation and translation pairs in or about each coordinate axis (Figures 3 and 4 above). Thus, CBP care is multi-modal and is consistent with Bolton’s ideas of clinical applications in evidence based practice.45 Table 2 outlines treatment interventions recommended by CBP for each of relief and structural rehabilitative care.

The reason for postural mirror imageÒ exercises, adjustments, and traction procedures is to address all the tissues involved in spine and posture alignment.

Unlike the relief care phase (approximately 12 visits), which includes segmental adjusting procedures from other named techniques, the E.A.T corrective care protocol is unique to CBP. In combination, these “E.A.T.” methods are unique to CBP Technique.

Table 2.

CBP recommended treatment methods for each phase of care, relief and structural rehabilitation of the spine and posture.

Frequency & Duration of CBP Technique Care

Previously it was stated that a typical patient is started with relief care at a frequency of 4 times per week for 3 weeks or 12 visits. After this 12 visit relief care regiment, a patient is re-evaluated to document improvements in initial (visit 1) positive exam findings, pain scales, disability indices, health status, and range of motion. Following this re-evaluation, the patient is transitioned into CBP structural rehabilitative E.A.T. procedures.4

To determine if the CBP E.A.T protocol of corrective care for each individual (based on his/her posture and spinal displacements) is achieving the desired normalization of posture and spinal alignment, re-examinations are suggested at 36 visit intervals. In other words after 24 visits of CBP E.A.T interventions added to the initial 12 visits of relief care. This 36 visit number is not based on personal opinion, but rather is an average duration from our six CBP clinical control trials.13-18 In order to arrive at this 36 visit time period, one could use a frequency of 4 visits per week for 9 weeks or 3 visits per week for 12 weeks.

In six clinical control trials detailing the outcomes of chronic pain patients with CBP Treatment interventions, the average chronic pain patient achieved a 75-80% improvement in their chronic pain and a 50% correction of their initial subluxated (abnormal spine alignment) position towards ideal and average spine alignment.13-18 This data indicates that, on average, a typical chronic pain patient may need 2 blocks of 36 visits of intensive structural rehabilitative care (defined as 3 or 4 visits per week) to achieve as near normal spinal alignment as possible.

Table 3.

CBP Protocol and Phases of Care showing the timing of different Treatment methods.

The frequency and duration of further care recommended to the patient at the 36 visit re-evaluation depends on their improvement in both structural and functional based outcomes. For example, if a patient achieves near-normal posture and spinal alignment at the 36 visit re-evaluation, then a reduced frequency of treatment is recommended for stabilization care (1-4 times per month depending upon the case). However, if at the first corrective care re-evaluation, less than average improvement is attained on comparative radiographs and postural examination (PosturePrint™), then this is indication that another block of 36 visits may be necessary for continued spinal correction. With CBP’s six completed clinical control trials, our methods have moved from the clinical opinion arena to having foundation in the category of “evidence based” care.

Conclusion

In our present era, ‘evidence-based’ medicine was coined as a means to improve patient outcomes and quality of care. CBP Technique uses postural and radiographic analysis procedures that have been shown to be reliable and valid. Significantly, CBP Technique has multiple types of peer-reviewed publications in scientific journals as evidence for its’ patient treatment methods. What remains for CBP technique is further refinement of technique protocols and evaluating the effects of subluxation reduction using the E.A.T. procedures in more advanced study designs. CBP is a technique practiced by a large number of practitioners, is a leader in the chiropractic technique and biomechanics research arena, and has shown good potential to improve chronic pain conditions in several patient populations and selected case studies.

References

-

Harrison DD. CBPâ Technique: The Physics of Spinal Correction. National Library of Medicine #WE 725 4318C, 1982-97. Harrison DD. CBP Technique: The Physiscs of Spinal Correction.

-

Harrison DD. Spinal Biomechanics: A Chiropractic Perspective. National Library of Medicine #WE 725 4318C, 1982-97. Harrison DD. CBP Technique: The Physiscs of Spinal Correction.

-

Harrison DD. CBP X-ray Work Book. National Library of Medicine #WE 725 4318C, 1982-97. Harrison DD. CBP Technique: The Physiscs of Spinal Correction.

-

Harrison DE, Harrison, DD, Haas JW. CBP® Structural Rehabilitation of the Cervical Spine. Evanston, WY: Harrison CBP Seminars, 2002.

-

Harrison DE, Harrison, DD, Haas JW, Oakley PA. Spinal Biomechanics for Clinicians, Volume I. Evanston, WY: Harrison CBP Seminars, 2003.

-

Harrison DE, Harrison, DD, Haas JW, Oakley PA. CBP® Structural Rehabilitation of the Lumbar Spine. Evanston, WY: Harrison CBP Seminars, 2005.

-

Harrison DE, Betz J, Harrison, DD. CBP® Structural Rehabilitation of the Thoracic Spine. Evanston, WY: Harrison CBP Seminars, 2005.

-

Chiropractic Biophysics Online. www.idealspine.com. Services/research papers. Accessed 12-15-04.

-

Harrison DD, Janik TJ, Harrison GR, Troyanovich SJ, Harrison DE, Harrison SO. Chiropractic Biophysics Technique: A Linear Algebra Approach to Posture in Chiropractic. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1996;19(8):525-535.

-

Panjabi MM, White AA, Brand RA. A Note on Defining Body Parts Configurations. J Biomech 1974; 7:385.

-

Harrison DE, Harrson DD. The Lumbar Spine: Rehabilitation with the CBPâ method. National Library of Medicine #WE 725 4318C, 1997.

-

Harrison DE, et al. Changes in sagittal lumbar configuration with a new method of extension traction. Presented at the 27th annual meeting of the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar spine. Adelaide, Australia April 9-13, 2000;151.

-

Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Cailliet R, Janik TJ, Holland B. Changes in Sagittal Lumbar Configuration with a New Method of Extension Traction: Non-randomized Clinical Control Trial. Arch Phys Med Rehab 2002;83(11):1585-1591.

-

Harrison DD, Jackson BL, Troyanovich SJ, Robertson GA, DeGeorge D, Barker WF. The Efficacy of Cervical Extension-Compression Traction Combined with Diversified Manipulation and Drop Table Adjustments in the Rehabilitation of Cervical Lordosis. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1994;17(7):454-464.

-

Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Betz J, Colloca CJ, Janik TJ, Holland B. Increasing the Cervical Lordosis with Seated Combined Extension-Compression and Transverse Load Cervical Traction with Cervical Manipulation: Non-randomized Clinical Control Trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2003; 26(3): 139-151.

-

Harrison DE, Cailliet R, Harrison DD, Janik TJ, Holland B. New 3-Point Bending Traction Method of Restoring Cervical Lordosis Combined with Cervical Manipulation: Non-randomized Clinical Control Trial. Arch Phys Med Rehab 2002; 83(4): 447-453.

-

Harrison DE, Cailliet R, Betz JW, Harrison DD, Haas JW, Janik TJ, Holland B. Harrison Mirror Image Methods for Correcting Trunk List: A Non-randomized Clinical Control Trial. Eur Spine J 2004; In Press.

-

Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Haas JW, Betz JW, Janik TJ, Holland B. Conservative Methods to Correct Lateral Translations of the Head: A Non-randomized Clinical Control Trial. J Rehab Res Devel 2004;41(4):631-640.

-

Zaleski BW, Wood J. A comparison of Palmer package and Chiropractic Biophysics for the treatment of pain. Proceedings of the International Conference on Spinal Manipulation 1992; Chicago, IL., May 15-17.

-

Paulk GP, Bennett DL, Harrison DE. Management of a chronic lumbar disk herniation with CBP methods following failed chiropractic manipulative intervention. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2005;in press.

-

Ferrantelli JR, Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Steward D. Conservative management of previously unresponsive whiplash associated disorders with CBP methods: a case report. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2005;in press.

-

Haas JW, Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Bymers B. Reduction of symptoms in a patient with syringomyelia, cluster headaches, and cervical kyphosis. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2005;in press.

-

Harrison DE, Bula J. Non-operative correction of the flexible flat back using lumbar extension traction: A case study of three. J Chiropractic Education 2002;16(1).

-

Bastecki A, Harrison DE, Haas JW. ADHD: A CBP case study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2004; 27(8):e14.

-

Harrison DE, Harrison DD. Chiropractic Biophysics Technique. Part I: The Scientific Basis. Eur Chiropractic J 2005;

-

Harrison DD, Janik TJ, Troyanovich SJ, Holland B. Comparisons of Lordotic Cervical Spine Curvatures to a Theoretical Ideal Model of the Static Sagittal Cervical Spine. Spine 1996;21(6):667-675.

-

Harrison DD, Harrison DE, Janik TJ, Cailliet R, Haas JW, Ferrantelli J, Holland B. Modeling of the Sagittal Cervical Spine as a Method to Discriminate Hypo-Lordosis: Results of Elliptical and Circular Modeling in 72 Asymptomatic Subjects, 52 Acute Neck Pain Subjects, and 70 Chronic Neck Pain Subjects. Spine 2004; 29:2485-2492.

-

Janik TJ, Harrison DD, Cailliet R, Troyanovich SJ, Harrison DE. Can the Sagittal Lumbar Curvature be Closely Approximated by an Ellipse? J Orthop Res 1998; 16(6):766-70.

-

Harrison DD, Cailliet R, Janik TJ, Troyanovich SJ, Harrison DE, Holland B. Elliptical Modeling of the Sagittal Lumbar Lordosis and Segmental Rotation Angles as a Method to Discriminate Between Normal and Low Back Pain Subjects. J Spinal Disord 1998; 11(5): 430-439.

-

Harrison DE, Janik TJ, Harrison DD, Cailliet R, Harmon S. Can the Thoracic Kyphosis be Modeled with a Simple Geometric Shape? The Results of Circular and Elliptical Modeling in 80 Asymptomatic Subjects. J Spinal Disord Tech 2002; 15(3): 213-220.

-

Harrison DD, Harrison DE, Janik TJ, Cailliet R, Haas JW. Do Alterations in Vertebral and Disc Dimensions Affect an Elliptical Model of the Thoracic Kyphosis? Spine 2003; 28(5):463-469.

-

Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Cailliet R, Troyanovich SJ, Janik TJ. Cobb Method or Harrison Posterior Tangent Method: Which is Better for Lateral Cervical Analysis? Spine 2000; 25: 2072-78.

-

Harrison DE, Cailliet R, Harrison DD, Janik TJ, Holland B. Centroid, Cobb or Harrison Posterior Tangents: Which to Choose for Analysis of Thoracic Kyphosis? Spine 2001; 26(11): E227-E234.

-

Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Janik TJ, Harrison SO, Holland B. Determination of Lumbar Lordosis: Cobb Method, Centroidal Method, TRALL or Harrison Posterior Tangents? Spine 2001; 26(11): E236-E242.

-

Harrison DE, Holland B, Harrison DD, Janik TJ. Further Reliability Analysis of the Harrison Radiographic Line Drawing Methods: Crossed ICCs for Lateral Posterior Tangents and AP Modified Risser-Ferguson. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2002; 25: 93-98.

-

Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Colloca CJ, Betz J, Janik TJ, Holland B. Repeatability of Posture Overtime, X-ray Positioning, and X-ray Line Drawing: An Analysis of Six Control Groups. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2003; 26(2): 87-98.

-

Haas M, Taylor JAM, Gillette RG. The routine use of radiographic spinal displacement analysis: a dissent. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1999;22:254-259.

-

Phillips RB. Plain film radiography in chiropractic. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1992;15:47-50.

-

Taylor JAM. Full-spine radiography: a review. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1993;16:460-474.

-

Kauffman JM. Diagnostic radiation: are the risks exaggerated? J Amer Phys Surg 2003;8(2):54-55.

-

Cohen BL, Lee IS. A catalog of risks. Health Physics 1979;36:707-722.

-

International Atomic Energy Agency. Facts about low-level radiation. American Nuclear Society, 1982.

-

Janik TJ, Harrison DE, Cailliet R, Harrison DD, Normand MC, Black P. Validity of an algorithm to estimate 3-D rotations and translations of the head in upright posture from three 2-D digital images. 2005; In Review.

-

Harrison DE, Janik TJ, Cailliet R, Harrison DD, Normand MC, Black P, Perron DL. Validation of an algorithm to estimate 3-D rotations and translations of the thorax and pelvis in upright posture from three 2-D digital images. 2005 In Review.

-

Bolton JE. The evidence in evidence-based practice: what counts and what doesn't count? J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2001;24:362-366.

-

Hrysomallis C, Goodman C. A review of resistance exercise and posture realignment. J Strength Cond Res 2001;15:385-390

-

Den Boer WA, Anderson PG, Limbek JV, Kooijman MAP. Treatment of idiopathic scoliosis with side shift therapy: An initial comparison with a brace treatment historical cohort. European Spine J 1999;8:406-410.

-

Weiss HR. Influence of an in-patient exercise program on scoliotic curve. Ital J Orthop Traumatol 1992; 18:395-406.

-

Weiss HR, Lohschmidt K, el-Obeidi N, Verres C. Preliminary results and worst-case analysis of in patient scoliosis rehabilitation. Pediatr Rehabil 1997;1:35-40.

-

Pearson ND, Walmsley RP. Trial into the effects of repeated neck retractions in normal subjects. Spine 1995; 20(11): 1245-51.).

-

DeVocht JW, Pickar JG, Wilder DG. EMG activity levels of paraspinal muscles during spinal manipulation. Proceedings from the 29th annual meeting of ISSLS 2002; Vancouver, Canada.

-

Oliver MJ, Twomey LT. Extension creep in the lumbar spine. Clin Biomech 1995;10:363-368.

29. Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Troyanovich SJ. Three-Dimensional Spinal Coupling Mechanics. Part II: Implications for Chiropractic Theories and Practice. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1998; 21(3): 177-86.

30. Harrison DE, Cailliet R, Harrison DD, Troyanovich SJ, Janik TJ. Cervical Coupling on AP Radiographs During Lateral Translations of the Head Creates an S-Configuration. Clin Biomech 2000; 15(6): 436-440.

31. Harrison DE, Cailliet R, Harrison DD, Janik TJ, Troyanovich SJ, Coleman RR. Lumbar Coupling During Lateral Translations of the Thoracic Cage Relative to a Fixed Pelvis. Clin Biomech 1999: 14(10):704-709.

Sunday, February 14, 2010 at 10:26AM

Sunday, February 14, 2010 at 10:26AM  CBP Seminars | Comments Off |

CBP Seminars | Comments Off |