The Cervical Lordosis in Health and Disease: Literature Review & The Denneroll 'Home Based' Orthotic

Monday, December 22, 2014 at 1:58PM

Monday, December 22, 2014 at 1:58PM  Deed E. Harrison, DC President CBP Seminars, Inc. Vice President CBP Non-Profit, Inc. Chair PCCRP Guidelines Editor—AJCC Private Practice-- Eagle, ID, USA

Deed E. Harrison, DC President CBP Seminars, Inc. Vice President CBP Non-Profit, Inc. Chair PCCRP Guidelines Editor—AJCC Private Practice-- Eagle, ID, USA

INTRODUCTION

Since my graduation from Chiropractic College (Life Chiropractic College West) in 1994, I’ve spent much of my 20 years in the clinical and research trenches attempting to understand and improve abnormalities of the cervical lordosis in patient populations. I've personally been involved in many scientific research investigations developing and discussing the evidence for the connection between the cervical lordosis in human health, disease, and spine disorders. In the current article, a brief but focused literature review on the cervical lordosis will be presented; then recommended in office vs. home care methods with the available evidence will be discussed.

The Adult Lordosis

The adult cervical lordosis has received considerable attention in the spine literature; in 1996, both average and idealized values and geometric shape of the cervical lordosis were reported. The average adult cervical lordosis was 34° ± 9° between C2-C7 posterior vertebral body lines.1 In a follow-up paper in 2004, my colleagues and I2 modeled the adult cervical lordosis (using a curve fitting method known as the least squares error) as a piece of a circle from C2-T1. Furthermore, we demonstrated statistically significant differences in adult cervical lordosis between normal subjects, acute neck pain subjects and chronic neck pain subjects.1,2

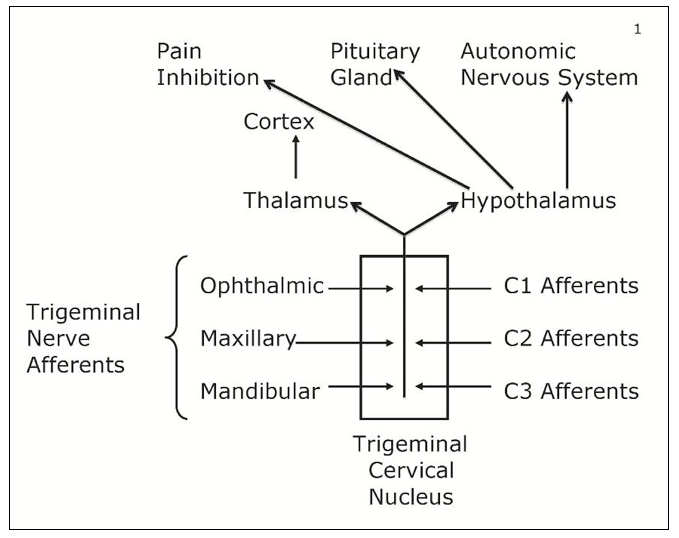

The Figure 1. below indicates the representative normal cervical lordosis.

Figure 1. ©Copyright Harrison CBP Seminars. Reprinted with permission.

Figure 1. ©Copyright Harrison CBP Seminars. Reprinted with permission.

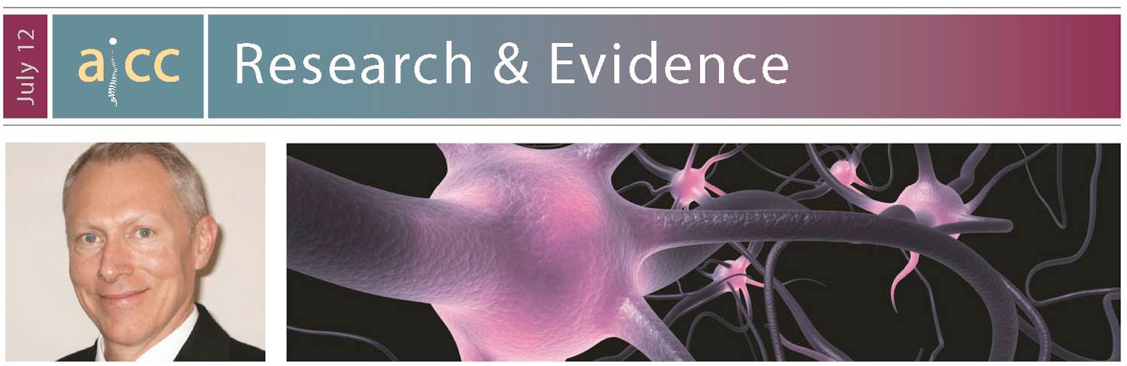

Literature Review Linking Lordosis to Disorders

Multiple investigations have been published seeking to understand the association, correlation, or the predictive value of an altered cervical lordosis in different health conditions compared to normal controls. To this end, the majority of these studies have found correlation and predictive validity of the lateral cervical radiographic alignment to a variety of health related conditions including:

- Acute and chronic neck pain.2-5

- Headaches.5-8

- Mental health status.9

- Whiplash associated disorders (WAD).10-18

- Degenerative joint disease (DJD).19-30

- Temporal mandibular joint disorders.31

- Range of motion and segmental motion patterns.32-34

- Respiration syndromes.35-39

- Radiculopathy.40,41

- Increased probability for soft tissue injury under impact and inertial loads.42-46

Oppositely, a few investigations have found that the lateral cervical alignment measurements do not correlate to and predict the findings in the above 10 categories.47-52 However, many of these investigations have been found to be internally flawed and detailed reviews of these studies have been performed.53-57 Thus, it should be obvious that the number (45 studies listed above) and the quality of investigations finding a correlation between the lateral cervical radiographic alignment and the conditions in the above 10 categories is superior to the few negative correlation studies. Over the past 20 years, I personally have concluded that the lateral cervical radiographic alignment has positive correlation and predictive validity for the above 10 categories of spine disorders and health conditions.

In Office Methods vs. At Home Care

Historically, the Chiropractic profession has a long history of interest in attempting to improve or correct alterations in cervical lordosis. Problematically, though many outcome investigations have been performed using a variety of chiropractic procedures, most of the traditional methods of Chiropractic procedures have been shown to have limited success at restoration of the cervical lordosis. Still, taken as a collective whole, these reports indicate that patients benefit by reduced pain, improved range of motion, decreased disability levels, and increased health status following chiropractic procedures that improve the cervical lordosis to near normal values.58-85

- § In Office Cervical Extension Traction Methods

According to the literature, Chiropractic BioPhysics® or CBP® Technique cervical extension traction procedures are the best available methods for conservatively, consistently and statistically, improving the cervical lordosis. This 'best' evidence exists as 4 clinical control trials (3 non-randomized and 1 randomized) where cervical extension traction treatment methods were added to and compared against various other chiropractic and physical procedures in treated patients versus control group populations.58-61 From this data, extension traction procedures have been found to produce average lordosis corrections between 7° (in more severely injured population) and 18° (in typical chronic neck pain populations) following approximately 36 treatment sessions over the course of 9-12 weeks duration.

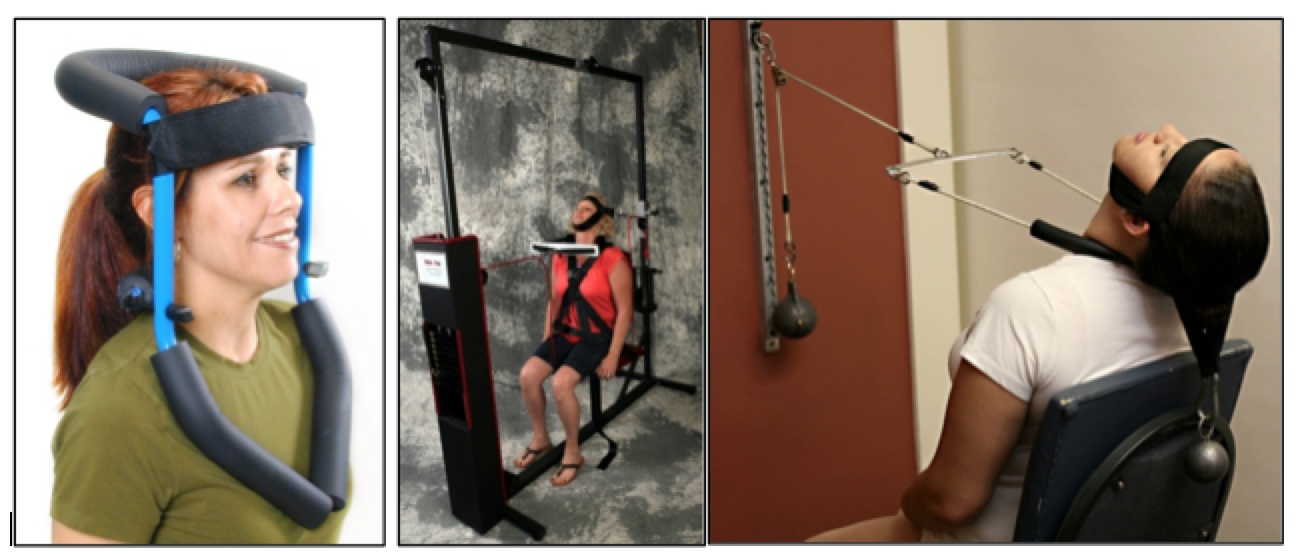

Though cervical extension traction procedures can be considered part of the standard of care for rehabilitation of the cervical lordosis; its wide spread implementation into Chiropractic practices has yet to occur. The likely reasons for this lack of widespread implementation for extension traction is multi-factorial and would include: increased square footage office space needed, increased staff to support implementation, increased patient time in the office, and lack of wide spread technical training for proper applications with indications and contraindications for the various methods. See Figure 2. for in office traction methods.

Figure 2. Various in office cervical extension traction methods. ©Copyright Harrison CBP Seminars. Reprinted with permission.

Figure 2. Various in office cervical extension traction methods. ©Copyright Harrison CBP Seminars. Reprinted with permission.

- § Home Corrective Orthotics

The use of home corrective orthotic (cervical curve traction) devices as a supplementation to in office treatment programs aimed at rehabilitation of abnormal cervical curvatures has a considerable history in Chiropractic practice. The use of 'at home' cervical extension traction orthotics would seemingly solve several of the key issues with implementation of in office traction methods. Home devices tend to be easier for the patient to use, they are less cumbersome, they are more affordable, and they are likely to be more tolerable. However, at least three main concerns with 'at home' based cervical orthotics must be acknowledged:

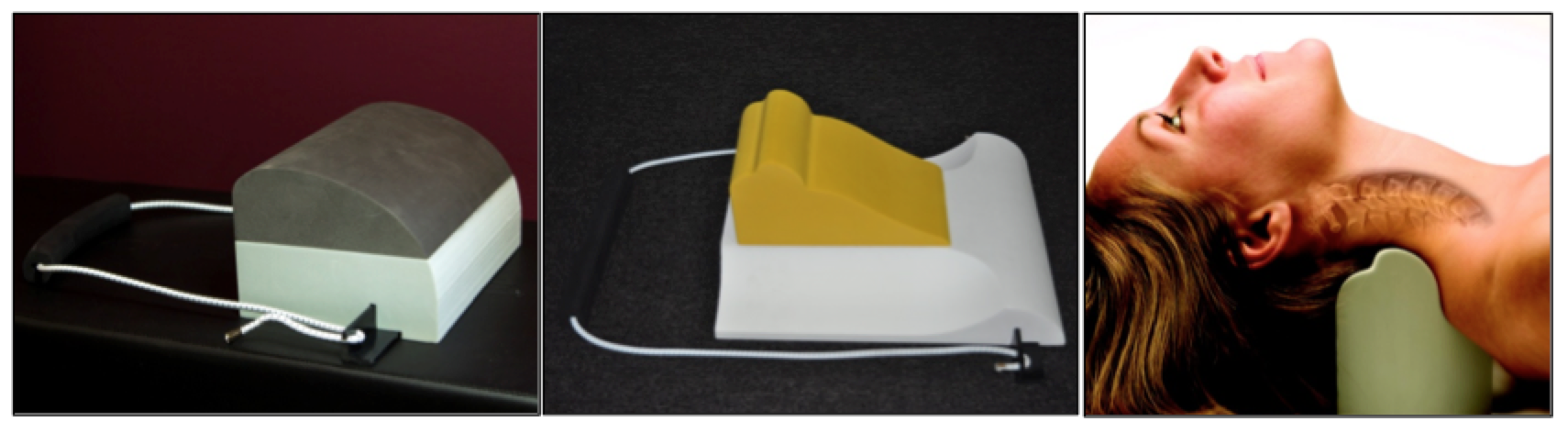

There are several different types of home based cervical lordosis corrective orthotics. In Figure 3. a couple of the more popular devices are depicted. Below, I've elected to focus on the cervical denneroll orthotic as it is one of the most applicable, easy to use, and effective (when used properly) home based orthotics today.

Figure 3. Various at home cervical extension traction orthotics: posture regainer, compression extension unit, and cervical denneroll. ©Copyright Harrison CBP Seminars. Reprinted with permission.

Figure 3. Various at home cervical extension traction orthotics: posture regainer, compression extension unit, and cervical denneroll. ©Copyright Harrison CBP Seminars. Reprinted with permission.

The Denneroll Cervical Orthotic

The cervical Denneroll orthotic device is a simple, yet complex, pillow-like device engineered with curves, angles, and ridges extrapolated, in part, from the CBP evidence based cervical spinal model. Adrian Dennewald, DC (Denneroll Industries in Sydney, Australia) is the developer and owner of the Denneroll orthotic line. In 2008, Dr. Adrian partnered with Chiropractic BioPhysics in an effort to expand the Denneroll product line, to develop proper indications and contraindications for patient care, and to research-test the effectiveness of the Denneroll in improving the cervical lordosis and patient conditions.

Personally, I was interested in the Cervical Denneroll device as a solution for a low-stress, comfortable mirror-image® traction orthotic to supplement CBP in office care at home.

To date, the cervical Denneroll, has been tested in a number of case reports and 2 randomized clinical trials. It's been found to improve the cervical lordosis in different patient populations by 7°-14°.86-91 Thus, the Denneroll orthtoic has been shown to be able to effectively improve the abnormal lordosis of the cervical spine in properly selected cases. Today, the cervical Denneroll products are used worldwide by over 5000 Chiropractors from North America and Australia to the UK, Europe, Asia, and several other international locations.

- Indications for the Denneroll

The Denneroll currently comes in 3 sizes (adult large, adult medium, and pediatric or small) and can be used in many patient conditions and cervical curve configureations. There are three primary placements of the Denneroll cervical orthotic device shown in Figures 4-6. The Denneroll placement should be consistent with both the shape of the cervical curve and the amount/type of sagittal head translation correction that is desired.

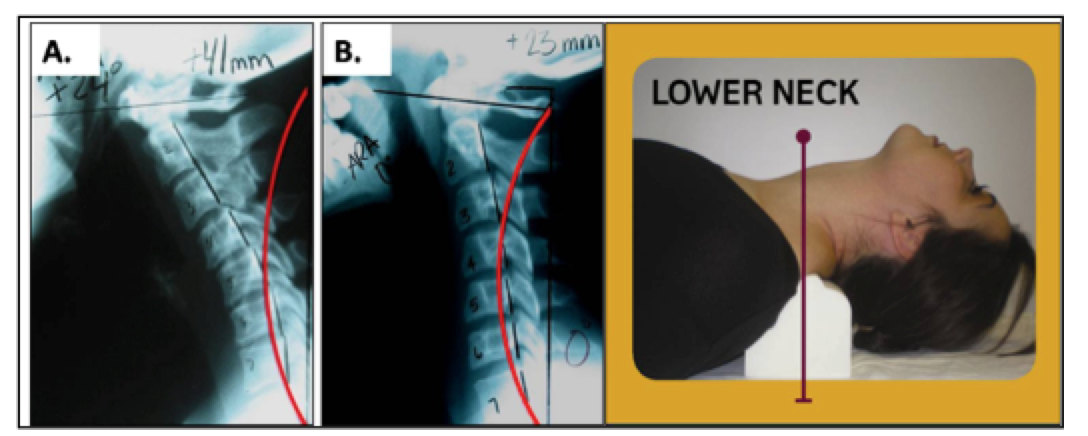

- Upper thoracic/lower cervical placement- C7-T2

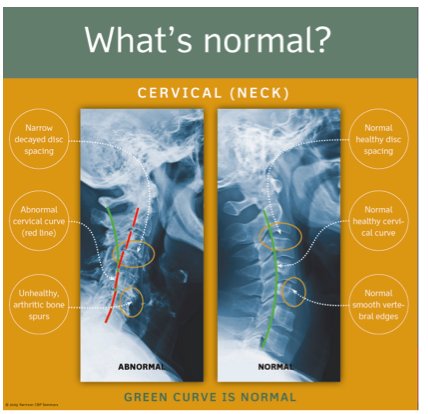

This placement of the Denneroll will cause significant posterior head translation, it will increase the upper thoracic curve, and increase the overall cervical lordosis. Specifically, this placement should be used for straightened or kyphotic lower cervical segments with loss of upper thoracic kyphosis and anterior head translation of ≤ 40mm. See Figure 4.

Figure 4. Abnormal cervical curvatures that fit the inclusion criteria for the application of the Denneroll corrective orthotic in the lower cervical region. These spines must have: • Normal or a mild loss of the upper thoracic kyphosis; • Loss of the lower cervical curve (with or without kyphosis); • Anterior head translation of approximately ≤ 40mm. ©Copyright Harrison CBP Seminars. Reprinted with permission.

Figure 4. Abnormal cervical curvatures that fit the inclusion criteria for the application of the Denneroll corrective orthotic in the lower cervical region. These spines must have: • Normal or a mild loss of the upper thoracic kyphosis; • Loss of the lower cervical curve (with or without kyphosis); • Anterior head translation of approximately ≤ 40mm. ©Copyright Harrison CBP Seminars. Reprinted with permission.

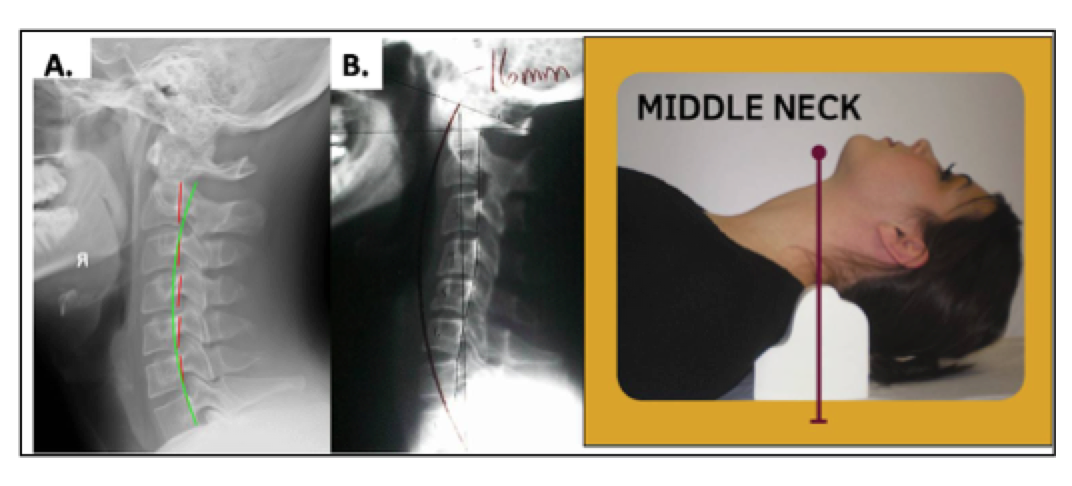

Mid-low cervical placement - C4-C6. This placement of the Denneroll will cause slight posterior head translation; however if the larger Denneroll device is used on a small statured individual then it will create some anterior head translation. The cervical spine should have straightened or kyphotic mid cervical regions (apex of the curve). See Figure 5. In cases with significant posterior head translation, as in Figure 5A, the large Denneroll orthotic should be used and a towel can be placed under the Denneroll to increase the height if needed.

Figure 5. Abnormal cervical curvatures that fit the inclusion criteria for the application of the Denneroll corrective orthotic in the middle cervical region. These spines must have: • Normal or a loss of the upper thoracic kyphosis; • Straightening or apex at the mid-cervical curve; • Slight anterior head translation of approximately ≤ 15mm; • In B with Posterior head translation the LARGE Denneroll should be used with a small towel under it to increase height. ©Copyright Harrison CBP Seminars. Reprinted with permission.

Figure 5. Abnormal cervical curvatures that fit the inclusion criteria for the application of the Denneroll corrective orthotic in the middle cervical region. These spines must have: • Normal or a loss of the upper thoracic kyphosis; • Straightening or apex at the mid-cervical curve; • Slight anterior head translation of approximately ≤ 15mm; • In B with Posterior head translation the LARGE Denneroll should be used with a small towel under it to increase height. ©Copyright Harrison CBP Seminars. Reprinted with permission.

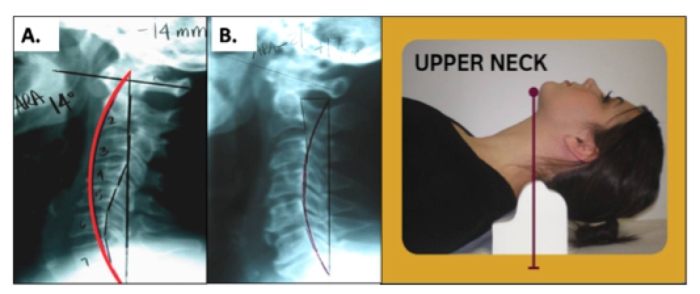

Upper to mid cervical placement- C2-C4. This placement of the Denneroll is used for posterior head translation with straightened or kyphotic mid-upper cervical curves. This position allows extension bending of the upper cervical segments while causing slight anterior head translation. See Figure 6. In cases like Figure 6A with significant posterior head translation, where the posterior vertebral bodies are behind the ideal red curved line,7 the large Denneroll orthotic should be used. While in Figure 6B, the small Denneroll should be used.

Figure 6. Abnormal cervical curvatures that fit the inclusion criteria for the application of the Denneroll corrective orthotic in the upper cervical region. These spines must have: • Close to normal lower cervical curvature; • Straightening or apex at the C2-C4-cervical segments; • In B, normal head translation of approximately ≤ 15mm. Here the SMALL Denneroll is used to not create anterior head posture; • In A with Posterior head translation the LARGE Denneroll should be used to create anterior head translation. ©Copyright Harrison CBP Seminars. Reprinted with permission.

Figure 6. Abnormal cervical curvatures that fit the inclusion criteria for the application of the Denneroll corrective orthotic in the upper cervical region. These spines must have: • Close to normal lower cervical curvature; • Straightening or apex at the C2-C4-cervical segments; • In B, normal head translation of approximately ≤ 15mm. Here the SMALL Denneroll is used to not create anterior head posture; • In A with Posterior head translation the LARGE Denneroll should be used to create anterior head translation. ©Copyright Harrison CBP Seminars. Reprinted with permission.

- Contra-indications for the Denneroll:

Quite simply put, no spine orthotic is indicated or should be used in every case presentation. There are both known and proposed risks for extension traction and extension positioning procedures in spine care. The treating -prescribing clinician should perform an examine in every case and perform proper tolerance testing with the patient prior to releasing the patient to use the Denneroll device at home.

Here's a basic proposed list of contra-indications for Denneroll orthotic patient use:

- Moderate to severe mid to upper thoracic hyper-kyphosis;

- Large, rigid anterior head translations that does not reduce with extension;

For a more complete list of contraindications for the Denneroll device, please consider the cervical Denneroll training DVD series available at this link: http://chiropractic-biophysics.myshopify.com/collections/denneroll-traction-devices/products/denneroll-box-set-all-5-dvds-cervical-thoracic-lumbar-compression-extension-and-scoliroll-training-videos

Simple Case Report for Understanding Home Care Implementation.

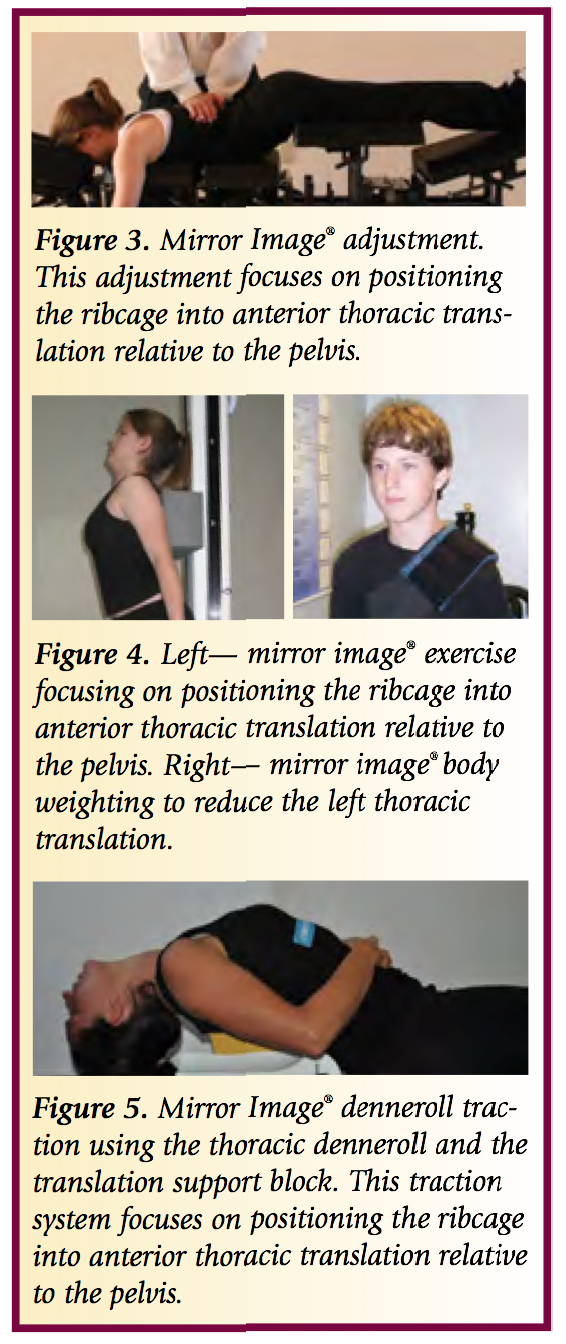

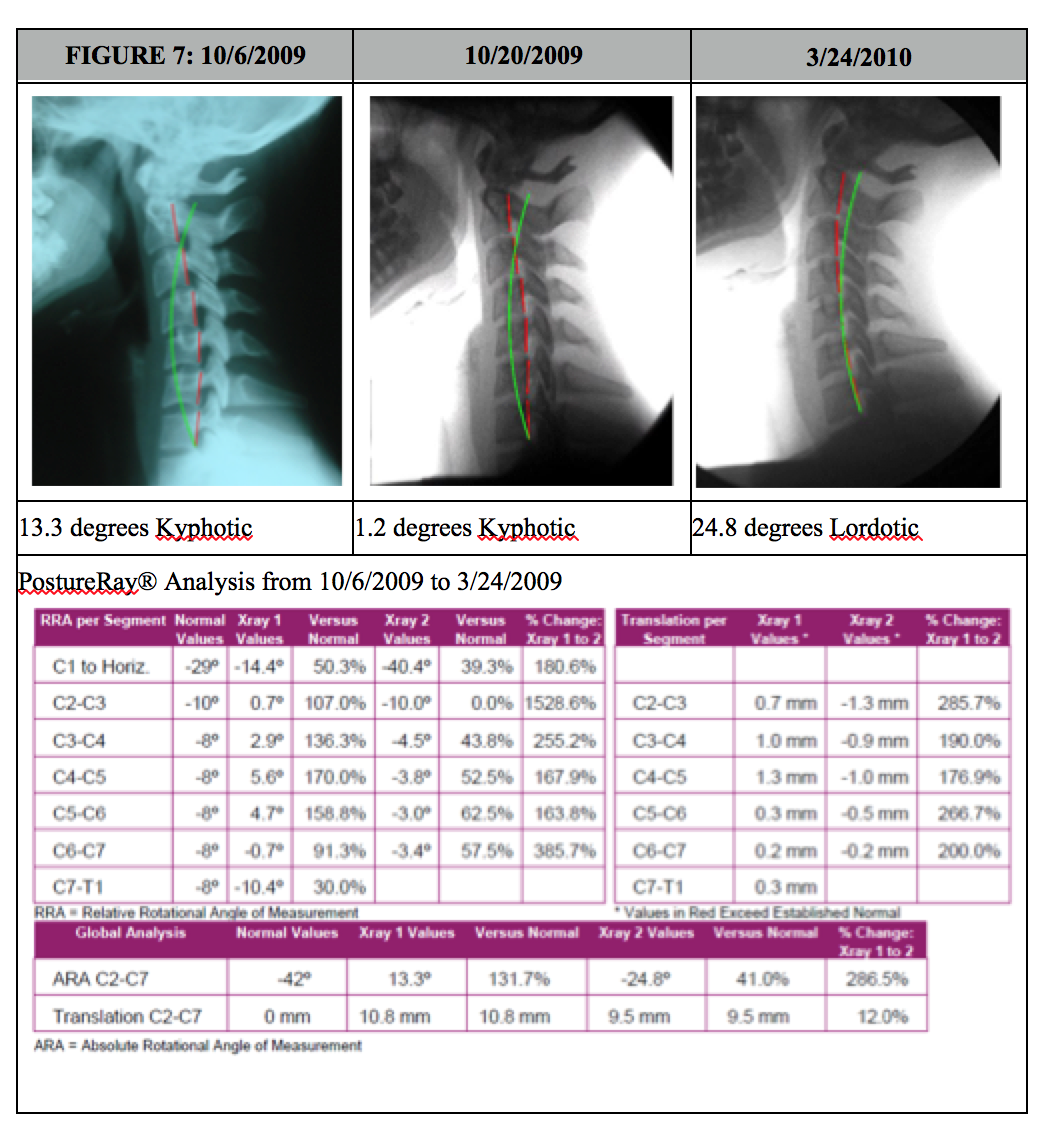

In this simple / brief case presentation, we have a female that was involved in a frontal collision crash. The subjective complaints were typical complaints seen with whiplash injuries, such as neck pain, sclerotome pain referral to lower neck and upper thoracic spine from probable facet joint injury, headaches, etc. In this case, the patient elected simply not to perform in office traction due to time constraints. In office care consisted of initial coarse of acute care diversified adjusting for 6 visits, then CBP Mirror Image® drop table and instrument based adjustments and Exercises. The patient having such a magnitude of kyphosis, was started as soon as possible with the Denneroll orthotic (on her 7th visit) starting 2x/day at 1 minute and building up to two sessions of 10 minutes, once in morning, and again once at night. Once this goal was achieved, after 2 weeks (4 weeks after injury), she was placed on 1 session of use per day working up to 20 minutes daily. Her initial x-ray was performed on 10/6/2009 then the next post was actually only 2 weeks later, this time on a Digital Motion X-Ray (DMX), dated 10/20/2009. DMX was chosen as she persisted with headaches and any evidence of ligamentous laxity can be documented. Notice in just 2 weeks of use, the cervical kyphosis is starting to reduce! After 40 sessions of home use, and 36 visits total treatments, with her symptoms and outcome studies showing her nearing pre-injury status, she was prescribed another follow up DMX. The changes on this final follow up x-ray (3-24-2010) were quite amazing as evidenced below in Figure 7.

A Recommendation for In Office & At Home Exercise Warm Up

It is usually more difficult to re-establish a cervical lordosis in patients that present with a kyphotic cervical curvature and moderate to advanced degenerative joint disease (DJD). These patients usually complain of chronic cervical pain, muscle rigidity and restricted motion. Many of these patients spend much of their day in cervical flexion or anterior head translation and have lost the capacity to truly extend and move their cervical spines. Long term relief for these patients is generally not possible without some form of effective structural and soft tissue rehabilitation.

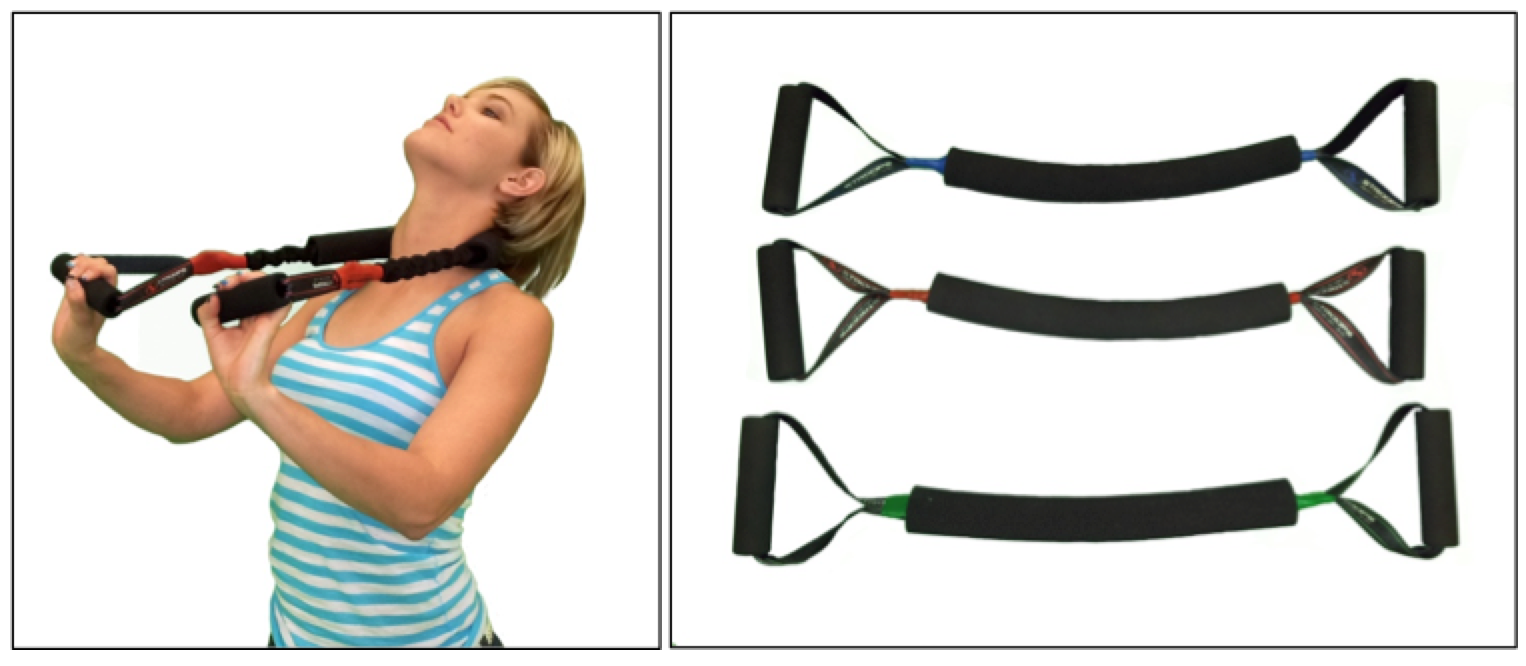

It is for the above reasons that we typically will recommend that patient performs a series of strengthening and flexibility exercises for their cervical spine prior to performing either in office cervical extension traction or at home Denneroll cervical extension traction. Most often we use the Pro-Lordoic Neck Exerciser™ developed by Dr. Don Meyer of California. This device was modified after the cervical neck strap used and taught for this exercise by myself in the CBP Cervical Rehab Seminars for the past several years. Typically we will have the patient perform various forms of cervical exercises using this exercise band for approximately 5-10 minutes prior to performing or using cervical extension traction devices. The Pro-Lordotic exerciser is shown in Figure 8.

A simple series of exercises with this band are shown on the below youtube links; however, it should be obvious that the treating clinician should select the proper exercises for the individual patient:

Figure 8. The Pro-Lordotic Neck Exerciser™ is a progressive resistance neck exercise device that tractions the normal lordosis into the cervical spine while active extension exercises of the entire cervical spine are performed during the five minute, structural/postural corrective, home or in-office treatment session. For product ordering information see the following link: http://chiropractic-biophysics.myshopify.com/collections/exercise-equipment/products/pro-lordotic-neck-exerciser ©Copyright Harrison CBP Seminars. Reprinted with permission.

Figure 8. The Pro-Lordotic Neck Exerciser™ is a progressive resistance neck exercise device that tractions the normal lordosis into the cervical spine while active extension exercises of the entire cervical spine are performed during the five minute, structural/postural corrective, home or in-office treatment session. For product ordering information see the following link: http://chiropractic-biophysics.myshopify.com/collections/exercise-equipment/products/pro-lordotic-neck-exerciser ©Copyright Harrison CBP Seminars. Reprinted with permission.

SUMMARY

Discussions of the cervical lordosis has a long history in the spine literature. While nothing is without controversy, the majority of past and present research reports indicate that the cervical lordosis plays a pivotal role in human health, many spine disorders, and several health disorders. While in office treatment programs combining cervical extension traction procedures should be considered the gold standard for consistent, predictable improvements in patients suffering from abnormalities of the cervical lordosis, at home based corrective cervical spine orthotics should be implemented as well. The cervical Denneroll is one of the most applicable, easy to use, most cost effective, and outcome effective home based cervical extension orthotics on the market today. Clinicians should be aware of the indications and contraindications for at home usage of this device. I hope this presentation assists in your delivery of effective patient intervention in the office and with supplementation of at home devices.

Note:

For more information on the Denneroll Orthotic, please visit http://www.idealspine.com/cervical-dennerol/

For information on becoming a denneroll provider in the USA / Canada please visit http://chiropractic-biophysics.myshopify.com/pages/signup.

References

1. Harrison DD, et al. Spine 1996; 21: 667-675.

2. Harrison DD, et al. Spine 2004; 29:2485-2492.

3. McAviney J, Schulz D, Richard Bock R, Harrison DE, Holland B. Determining a clinical normal value for cervical lordosis. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2005;28:187-193.

4. Jochumsen OH. The curve of the cervical spine. The ACA Journal of Chiropractic 1970; August IV:S49-S55.

5. Choudhary Bakhtiar S; Sapur Suneetha; Deb P S. Forward Head Posture is the Cause of 'Straight Spine Syndrome' in Many Professionals. Indian J Occupat and Environmental Med 2000 (Jul); 4 (3): 122—124.

6. Nagasawa A, Sakakibara T, Takahashi A. Roentgenographic findings of the cervical spine in tension-type headache. Headache 1993;33:90-95.

7. Braaf MM, Rosner S. Trauma of the cervical spine as a cause of chronic headache. J Trauma 1975;15:441-446.

8. Vernon H, Steiman I, Hagino C. Cervicogenic dysfunction in muscle contraction headache and migraine: A descriptive study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1992;15:418-29.

9. Mears DB. Mental disease and cervical spine distortions. The ACA Journal of Chiropractic 1965; September, pages:13-16,44-46.

10. Kai Y, Oyama M, Kurose S, et al. Traumatic thoracic outlet syndrome. Orthop Traumatol 1998;47:1169-1171.

11. Giuliano V, Giuliano C, Pinto F, Scaglione M. The use of flexion and extension MR in the evaluation of cervical spine trauma: initial experience in 100 trauma patients compared with 100 normal subjects. Emergency Radiology 2002;9:249-253.

12. Giuliano V, Giuliano C, Pinto F, Scaglione M. Soft tissue injury protocol (STIP) using motion MRI for cervical spine trauma assessment. Emergency Radiology 2004;10:241-245.

13. Marshall DL, Tuchin PJ. Correlation of cervical lordosis measurement with incidence of motor vehicle accidents. ACO 1996;5(3):79-85.

14. Norris SH, Watt I. The prognosis of neck injuries resulting from rear-end vehicle collisions. J Bone and Joint Surgery 1983;65-B:608-611.

15. Hohl M. Soft-tissue injuries of the neck in automobile accidents. J Bone and Joint Surgery 1974;56-A:1675-1682.

16. Zatzkin HR, Kveton FW. Evaluation of the cervical spine in whiplash injuries. Radiology 1960;75:577-583.

17. Kristjansson E, et al. Is the Sagittal configuration of the cervical spine changed in women with chronic whiplash syndrome? A comparative computer-assisted radiographic assessment. JMPT 2002;25:550-555.

18. Griffiths HJ, Olson PN, Everson LI, Winemiller M. Hyperextension strain or "whiplash" injuries to the cervical spine. Skeletal Radiology 1995; 24(4):263-6.

19. Yoon T, Natarajan R, An H, et al. Adjacent disc biomechanics after anterior cervical diskectomy and fusion in kyphosis. Presented at Cervical Spine Research Society, Charleston, SC, Nov. 30-Dec. 2, 2000.

20. Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Janik TJ, Jones EW, Cailliet R, Normand M. Comparison of axial flexural stresses in lordosis and three buckled configurations of the cervical spine. Clin Biomech 2001;16:276-284.

21. Harrison DE, Jones EW, Janik TJ, Harrison DD. Evaluation of axial and flexural stresses in the vertebral body cortex and trabecular bone in lordosis and two sagittal cervical translation configurations with an elliptical shell model. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2002;26:391-401.

22. Matsunaga S, Sakou T, Sunahara N, et al. Biomechanical analysis of buckling alignment of the cervical spine: predictive value for subaxial subluxation after occipitocervical fusion. Spine 1997; 22: 765-71.

23. Matsunaga S, Sakou T, Taketomi E, Nakanisi K. Effects of strain distribution in the intervertebral discs on the progression of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligaments. Spine 1996;21:184-189.

24. Katsuura A, et al. Kyphotic malalignment after anterior cervical fusion is one of the factors promoting the degenerative process in adjacent intervertebral levels. Eur Spine J 2001;10:320-324.

25. Matsunaga S, et al. Significance of occipitoaxial angle in subaxial lesion after occipitocervical fusion. Spine 2001;26:161-165.

26. Matsunaga S, Sakou T, Nakanisi K. Analysis of the cervical spine alignment following laminoplasty and laminectomy. Spinal Cord 1999;37:20-24.

27. Vavruch L, Hedlund R, Javid D, Leszniewski W, Shalabi A. A prospective randomized comparison between the Cloward Procedures and a carbon fibre cage in the cervical spine: a clinical and radiological study. Spine 2002; 27:1694-1701.

28. Borden AGB, Rechtman AM, Gershon-Cohen J. The normal cervical lordosis. Radiology 1960;74:806-810.

29. Harrison DD, Harrison DLJ. Pathological stress formations on the anterior vertebral body in the cervicals. In: Suh CH, ed. The proceedings of the 14th annual biomechanics conference on the spine. Mechanical Engineering Dept., Univ. of Colorado, 1983:31-50.

30. Yu JK. The relationship between experimental changes in the stress-strain distribution and the tissues structural abnormalities of the cervical column Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 1993 Aug;31(8):456-9.

31. D'Attilio M, Epifania E, Ciuffolo F, Salini V, Filippi MR, Dolci M, Festa F, Tecco S. Cervical lordosis angle measured on lateral cephalograms; findings in skeletal class II female subjects with and without TMD: a cross sectional study. Cranio. 2004 Jan;22(1):27-44.

32. Panjabi MM, Oda T, Crisco JJ, Dvorak J, Grob D. Posture affects motion coupling patterns of the upper cervical spine. J Orthop Res 1993;11:525-536.

33. Takeshima T, Omokawa S, Takaoka T, Araki M, Ueda Y, Takakura Y. Sagittal alignment of cervical flexion and extension: Lateral radiographic analysis. Spine 2002;27:E348-355.

34. Miller JS, Polissar NL, Haas M. A radiographic comparison of neutral cervical posture with cervical flexion and extension ranges of motion. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1996 Jun;19(5):296-301.

35. Ozbek MM, Miyamoto K, Lowe AA, Fleetham JA. Natural head posture, upper airway morphology and obstructive sleep apnoea severity in adults. Eur J Orthod 1998;20:133-143.

36. Tangugsorn V, Skatvedt O, Krogstad O, Lyberg T. Obstructive sleep apnoea: a cephalometric study, part I. Cervico-craniofacial skeletal morphology. Eur J Orthod 1995;17:45-56.

37. Hellsing E. Changes in the pharyngeal airway in relation to extension of the head. European J Orthodontics 1989;11:359-365.

38. Kuhn D. A Descriptive Report of Change in Cervical Curve in a Sleep Apnea Patient: The Importance of Monitoring Possible Predisposing Factors in the Application of Chiropractic Care. JVSR 1998 Vol 3, No. 1, p 1-9.

39. Dobson, GJ.; Blanks, RHI.; Boone, WR.; Mccoy, HG.; Cervical Angles in Sleep Apnea Patients: A Retrospective Study. JVSR 1999; 3(1): 9-23.

40. Ferch RD, Shad A, Cadoux-Hudson TA, Teddy PJ. Anterior correction of cervical kyphotic deformity: effects on myelopathy, neck pain, and sagittal alignment. J Neurosurg Spine. 2004;100(1):13-19.

41. Harwant S. Relevance of Cobb method in progressing sagittal plane spinal deformity. Med J Malaysia. 2001 Dec;56 Suppl D:48-53.

42. Stemper BD, Yohanandan N, Pintar FA. Effects of abnormal posture on capsular ligament elongations in a computational model subjected to whiplash loading. J Biomechanics 2005;38:1313-1323.

43. Frechede B, Saillant G, LaVaste F, Skalli W. Risk of injury of the human neck during impact: role of geometrical and mechanical parameters. Paper A29; Presented at the European Cervical Spine Research Society Annual Meeting; 2004 Porto, Portugal, May 30-June 5.

44. Oktenoglu T, Ozer AF, Ferrara LA, Andalkar N, Sarioglu AC, Benzel EC. Effects of cervical spine posture on axial load bearing ability: a biomechanical study. J Neurosurg (Spine 1) 2001; 943:108-114.

45. Swartz EE, Floyd RT, Cendoma M. Cervical spine functional anatomy and the biomechanics of injury due to compressive loading. J Athletic Training 2005;40(3):155-161.

46. Maiman DJ, Yoganandan N, Pintar FA. Preinjury cervical alignment affecting spinal trauma. J Neurosurg. 2002 Jul;97(1 Suppl):57-62.

47. Gay RE. The curve of the cervical spine: variations and significance. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1993;16:591-594.

48. Mamairas C, Barnes MR, Allen MJ. “Whiplash injuries” of the neck: a retrospective study. Injury 1998;19:393-396.

49. Haas M, Taylor JAM, Gillete RG. The routine use of radiographic spinal displacement analysis: A dissent. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1999;22:254-59.

50. Gore DR, Sepic SB, Gardner GM. Roentgenographic findings of the cervical spine in asymptomatic people. Spine 1986;11:521-524.

51. Peterson CK, et al. Prevalence of hyperplastic articular pillars in the cervical spine and relationship with cervical lordosis. J Manipulative and Physiol Ther 1999;22:390-394.

52. Li YK, Zhang YK, Zhong SZ. Diagnostic value on signs of subluxation of cervical vertebrae with radiological examination. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1998; 21(9):617-20.

53. Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Troyanovich SJ. Reliability of Spinal Displacement Analysis on Plane X-rays: A Review of Commonly Accepted Facts and Fallacies with Implications for Chiropractic Education and Technique. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1998;21:252-66.

54. Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Troyanovich SJ. A Normal Spinal Position, Its Time to Accept the Evidence. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2000;23: 623-644.

55. Harrison DE. Counter-point article-A Selective Literature Review, Misrepresentation of Studies, & Side Stepping Spine Biomechanics Lead to an Inappropriate Characterization of CBP Technique. AJCC January 2005.

56. Harrison DE. Counter-point article-A Selective Literature Review, Misrepresentation of Studies, & Side Stepping Spine Biomechanics Lead to an Inappropriate Characterization of CBP Technique. Part II. AJCC April 2005.

57. Harrison DE, Haas JW, Harrison DD, Janik TJ, Holland B. Do Sagittal Plane Anatomical Variations (Angulation) of the Cervical Facets and C2 Odontoid Affect the Geometrical Configuration of the Cervical Lordosis? Results from Digitizing Lateral Cervical Radiographs in 252 neck pain subjects. Clin Anat 2005; 18:104-111.

58. Harrison DD, Jackson BL, Troyanovich SJ, Robertson GA, DeGeorge D, Barker WF. The Efficacy of Cervical Extension-Compression Traction Combined with Diversified Manipulation and Drop Table Adjustments in the Rehabilitation of Cervical Lordosis. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1994;17(7):454-464

59. Harrison DE, Cailliet R, Harrison DD, Janik TJ, Holland B. New 3-Point Bending Traction Method of Restoring Cervical Lordosis Combined with Cervical Manipulation: Non-randomized Clinical Control Trial. Arch Phys Med Rehab 2002; 83(4): 447-453.

60. Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Betz J, Janik TJ, Holland B, Colloca C. Increasing the Cervical Lordosis with CBP Seated Combined Extension-Compression and Transverse Load Cervical Traction with Cervical Manipulation: Non-randomized Clinical Control Trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2003; 26(3): 139-151.

61. Ibrahim M, Aliaa AD, Ahmed A, Harrison DE. THE EFFICACY OF CERVICAL LORDOSIS REHABILITATION FOR NERVE ROOT FUNCTION, PAIN, AND SEGMENTAL MOTION IN CERVICAL SPONDYLOTIC RADICULOPATHY Physiotherapy 2011; 97:supplement 1: 846-847.

62. Khorshid KA, Sweat RW, Zemba DA, Zemba BN. Clinical Efficacy of Upper Cervical Versus Full Spine Chiropractic Care on Children with Autism: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JVSR March 9, 2006, pp 1-7.

63. Wallace HL, Jahner S, Buckle K, Desai N. The relationship of changes in cervical curvature to visual analog scale, neck disability index scores and pressure algometry in patients with neck pain. Chiropractic: J Chiropractic Res Clin Invest 1994; 9:19-23.

64. Troyanovich SJ, Harrison DD, Harrison DE. A Review of the Validity, Reliability, and Clinical Effectiveness of Chiropractic Methods Employed to Restore or Rehabilitate Cervical Lordosis. Chiropr Tech 1998; 10(1): 1-7.

65. Alcantara J, Heschong R, Plaugher G, Alcantara. Chiropractic management of a patient with subluxations, low back pain and epileptic seizures. J Manipulative and Physiol Ther 1998;21:410-418.

66. Alcantara J, Plaugher G, Thornton RE, Salem C. Chiropractic care of a patient with vertebral subluxations and unsuccessful surgery of the cervical spine. J Manipulative and Physiol Ther 2001;24:477-482.

67. Alcantara J, Steiner DM, Gregory Plaugher and Joey Alcantara .Chiropractic management of a patient with myasthenia gravis and vertebral subluxations. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1999;22:333–40.

68. Alcantara J, Plaugher G, Van Wyngarden DL. Chiropractic care of a patient with vertebral subluxation and Bell's palsy. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2003 May;26(4):253.

69. Araghi HJ. Juvenile Myasthenia Gravis: A Case Study in Chiropractic Management (1993 Proceedings) http://www.icapediatrics.com/reference-journals.php#.

70. Araghi HJ Post-traumatic Evaluation and Treatment of The Pediatric Patient with Head Injury: A Case Report (1992 Proceedings) http://www.icapediatrics.com/reference-journals.php#.

71. Kessinger RC, Boneva DV. Case study: Acceleration/deceleration injury with angular kyphosis. J Manipulative and Physiol Ther 2000; 23:279-287.

72. Bastecki A, Harrison DE, Haas JW. ADHD: A CBP case study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2004; 27(8): 525e1-525e5.

73. Ferrantelli JR, Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Steward D. Conservative management of previously unresponsive whiplash associated disorders with CBP methods: a case report. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2005; 28(3): e1-e8.

74. Haas JW, Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Bymers B. Reduction of symptoms in a patient with syringomyelia, cluster headaches, and cervical kyphosis: A CBP® case report. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2005; 28(6):452.

75. Colloca CJ, Polkinghorn BS. Chiropractic management of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome: A report of two cases. JMPT 2003;26:448-459.

76. Coleman RR, Hagen JO, Troyanovich SJ, Plaugher G. Lateral cervical curve changes receiving chiropractic care following a motor vehicle collision: A retrospective case series. J Manipulative Physiol Therap 2003;26:352-355.

77. Morningstar, MW. Cervical hyperlordosis, forward head posture, and lumbar kyphosis correction: a novel treatment for mid-thoracic pain. J Chiropr Med 2003 Sept;(2:3):111-115.

78. Morningstar, MW. Cervical curve restoration and forward head posture reduction for the treatment of mechanical thoracic pain using the Pettibon corrective and rehabilitative procedures. J Chiropr Med 2002 Sept;(1:3):113-115.

79. Morningstar, M.W.; Strauchman, M.N.; Weeks, D.A.; Spinal Manupulation and Anterior Headweighting for the Correction of Forward Head Posture and Cervical Hypolordosis: A Pilot Study. J Chiropr Med 2003; 2(2):51-54.

80. Pierce VP. Results I. Dravosburg, PA: CHIRP, Inc., 1981.

81. Reynolds, C.; Reduction of Hypolordosis of the Cervical Spine and Forward Head Posture with Specific Adjustment and the Use of a Home Therapy Cushion. Chiropractic Research Journal 1998; 5(1):23-7.

82. Gary Knutson, DC and Moses Jacob, DC. Possible manifestation of temporomandibular joint dysfunction on chiropractic cervical x-ray studies. J Manipulative Physiol Ther: JAN 1999(22:1) Page(s) 32-37.

83. Moore MK. Upper crossed syndrome and its relationship to cervicogenic headache. J Manipulative Physiol Ther: JUL/AUG 2004(27:6).

84. Dobson GJ. Structural Changes in the Cervical Spine Following Spinal Adjustments in a Patient with Os Odontoideum: A Case Report. JVSR August 1996, Vol 1, No. 1, p 1-12.

85. Moore MK. Upper crossed syndrome and its relationship to cervicogenic headache. J Manipulative Physiol Ther: JUL/AUG 2004(27:6).

86. Paris B, Harrison DE. Restoration of an Abnormal Cervical Lordosis Using the DENNEROLL: A CBP® Case Report. American Journal of Clinical Chiropractic (ISSN 1076- 7320) 2010; April Vol.20 (2):14,26. http://www.chiropractic-biophysics.com/clinical_chiropractic/2010/4/12/restoration-of-an-abnormal-cervical-lordosis-using-the-denne.html

87. Ferrantelli JR. BioPhysics Insights: The Denneroll Orthotic. American Journal of Clinical Chiropractic (ISSN 1076-7320) 2010; July Vol.20 (3): 13-14. http://www.chiropractic-biophysics.com/clinical_chiropractic/2010/9/12/the-denneroll-orthotic-i-didnt-believe-it-till-i-tried-it.html

88. Ferrantelli JR, Harrison DE. Denneroll Combined with Pope 2-Way Aids Patient Suffering from Chronic Whiplash Associated Disorders & Advanced S.A.D.D. American Journal of Clinical Chiropractic (ISSN 1076-7320) 2010; Oct. Vol.20 (4):13,14. http://www.chiropractic-biophysics.com/clinical_chiropractic/2010/10/22/denneroll-combined-with-pope-2-way-aids-patient-suffering-fr.html

89. Boyd C, Harrison DE. CBP Chiropractors: We Must Practice What We Teach American Journal of Clinical Chiropractic (ISSN 1076-7320) 2012: http://www.chiropractic-biophysics.com/clinical_chiropractic/2012/4/1/cbp-chiropractors-we-must-practice-what-we-teach.html

90. Does improvement towards a normal cervical sagittal configuration aid in the management of lumbosacral radiculopathy: a randomized controlled trial. In Review for possible publication.

91. The Effect of Normalizing the Cervical Sagittal Configuration for the Management of Cervicogenic Dizziness: A 1-Year Randomized Controlled Study. In Review for possible publication.

CBP Seminars | Comments Off |

CBP Seminars | Comments Off |  CBP,

CBP,  CBP Research,

CBP Research,  Denneroll Orthotic

Denneroll Orthotic