Treating the Elderly with Chiropractic BioPhysics® or CBP® Technique Methods

Sunday, January 11, 2015 at 4:52PM

Sunday, January 11, 2015 at 4:52PM Jason W. Haas, DC

Private Practice Windsor, CO

Many practitioners are surprised to find out the extent of Chiropractic BioPhysics or CBP Technique methods we employ to treat elderly patients in our facility. Some colleagues feel that the elderly patients may not be a candidate for treatment due to the fact that they are older, frailer, can have extensive degeneration or many comorbidities.1-3 These doctors are afraid to attempt to change their spine and posture because the problem is long-standing or they fear they may injure the patient. However, in our clinical experience treating over 6500 patients in the last eleven years, we have found that the elderly patients respond very well to gentle application of CBP methods and astute clinicians will find that they can have a tremendous positive effect on a patient’s posture, pain, quality of life and overall health.

Most of our elderly patients come to us for painful conditions that they have not been able to find relief from using traditional treatments of drugs, surgery or even traditional chiropractic and physical therapy. These patients are often discouraged with healthcare in general because they are finding that the time they spend with their doctor is less and less and the outcomes of the medicines they are prescribed are less and less effective. This can create a situation of frustration that a well-trained receptionist must contend with in order to get the elderly person feeling comfortable in the office. A great tour of the office and a compassionate staff can show these folks that the CBP experience will likely be completely different from other chiropractors, medical doctors and other healthcare providers

Our Intake Process & General Exam Procedures

Once they see that we offer a different approach to spinal care, we can move them through the process of intake. The examination is similar to younger patients but may require more time due to a longer health history and multiple concomitant health concerns/conditions. We will always perform a thorough health history, all pertinent orthopedic and neurological testing, blood analysis if necessary, CBP structural evaluation including spine and extremity films when indicated, Posture Screen™ digital postural analysis and all pertinent outcome measures (all patients receive the SF-36, pain and disability questionnaires), and digital range of motion and strength testing.

Once we have the data for our initial assessment we make a determination as to whether they are candidates for CBP Structural Rehabilitation; yes there are some cases that we won't perform CBP care with due to contra-indications. This assessment involves looking at the evaluated spine films with PostureRay™, and determining if there are any areas that would not respond well to conservative care, and CBP care especially. If there are areas of suspected instability we will take flexion/extension films or send to my friend Evan Katz,DC for DMX. Once possible contraindications have been ruled out, we explain the importance of improving sagittal and coronal balance with the patient and discuss the limitations that the care may have. The discussions on limitations are crucially important because the elderly patients must be aware that osteophytes, disc and ligament degeneration and severe structural abnormalities will likely not return to normal as a result of the care we are providing. They must know that the goals are better range of motion and strength, better posture (coronal and sagittal) and improvements measured on their outcome measures (SF-36, NDI, etc.) If a patient has an unrealistic expectation of being “fixed” and getting back to completely normal, it’s important to inject some reality and sometimes limit expectations.

Sagittal Plane Alignment & Health Concerns in the Elderly

The sagittal plane alignment of the spine and posture and it's connection to human health and longevity is becoming one of the most widely researched topics in spine care today.4-10 The sagittal plane alignment of the spine and posture in the elderly has been found to correlate to the following health disorders:

- Increased risk of spinal compression fractures;4

- Increased low back pain and more severe pain;5

- Decreased mobility and increased risk of falls leading to fractures;6,7,8

- Increased risk of going into a care giving facility and not being able to take care of one's self in normal activities of daily living;9

- Increased knee or patellar femoral pain;10

- Increased disability and impairment due to pain;11

- Possible increase risk of early death compared to age match corhorts.12,13

For example, of a few of these important studies are reviewed here. Kobayashi and colleagues4 prospectively followed 100 subjects aged 61.9 yrs of age for an additional 12 years (indicating they were about 74 years at follow up). Full spine radiographs were ascertained at initial and long-term follow up in an attempt to identify if sagittal plane radiographic alignment variables play a role in the risk for developing new vertebral compression fractures. In both univariate and multivariate analysis, reductions in lumbar lordosis (Cobb L1-L5) and thoracic kyphosis (Cobb T4-T12) increased the relative risk of developing a new vertebral body compression fracture. Significantly, even curves one standard deviation below the mean value showed statistically significant increased relative risks (RR 3.06). Their4 most statistically significant model was multi-variate including pre-existing compression fractures with both the lumbar lordosis and thoracic kyphosis decreased (RR 8.64). Kobayashi and colleagues4 suggested that flattened curves reduce the shock absorbing capability of the sagittal curves, increasing the dynamic loads on the vertebral bodies thus increasing the risk of fractures.

In a prospective study of 253 chronic LBP patients matched by age and physical characteristics to 253 normal controls between the ages of 50-85 years, Tsuji et al5 found a reduced L1-S1 lordosis in the chronic LBP group. Of primary importance, lumbar lordosis was inversely correlated with pain intensity on a visual analog scale (p= 0.025). In other words, as the lumbar lordosis decreased, the pain intensity of the subject was increased.5

Recently, Kamitami et al9, studied the spinal posture in 804 participants (65–94 yrs of age) who were initially independent in their activities of daily living (ADLL) at baseline. These participants were followed for a 4.5-year follow-up period and it was found that 126 (15.7%) of the participants became dependent in their ADLs. Dependence in ADL was defined as admission to a nursing home or need of home assistance to perform basic self care functions. Importantly, inclination of the upper body relative to the pelvis (angle subtended between the vertical and a line joining C7 to the sacrum) was correlated with outcome and lumbar curvature also showed a marginal association. After adjusting for age and sex, it was found that for each 1 unit increase in the quartile of forward inclination that the odds of becoming dependent on ADL's was 1.79 x greater. Indicating that the highest quartile had a risk of 1.79 x 3 = 5.37 times more likely to be dependent. This study is very important for the elderly person wanting to remain able to perform basic care functions.

Chiropractic BioPhysics Mirror Image® Treatment Approach

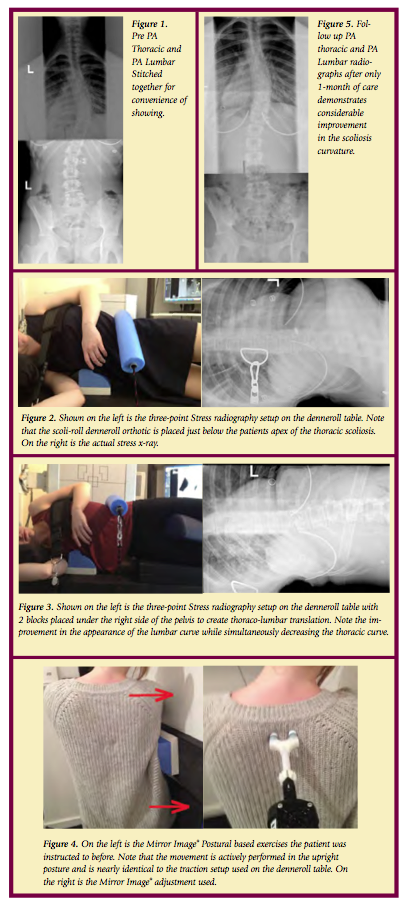

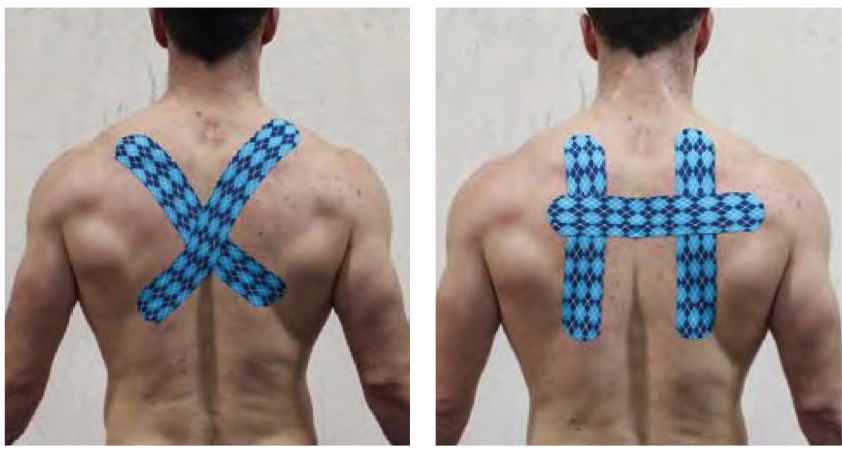

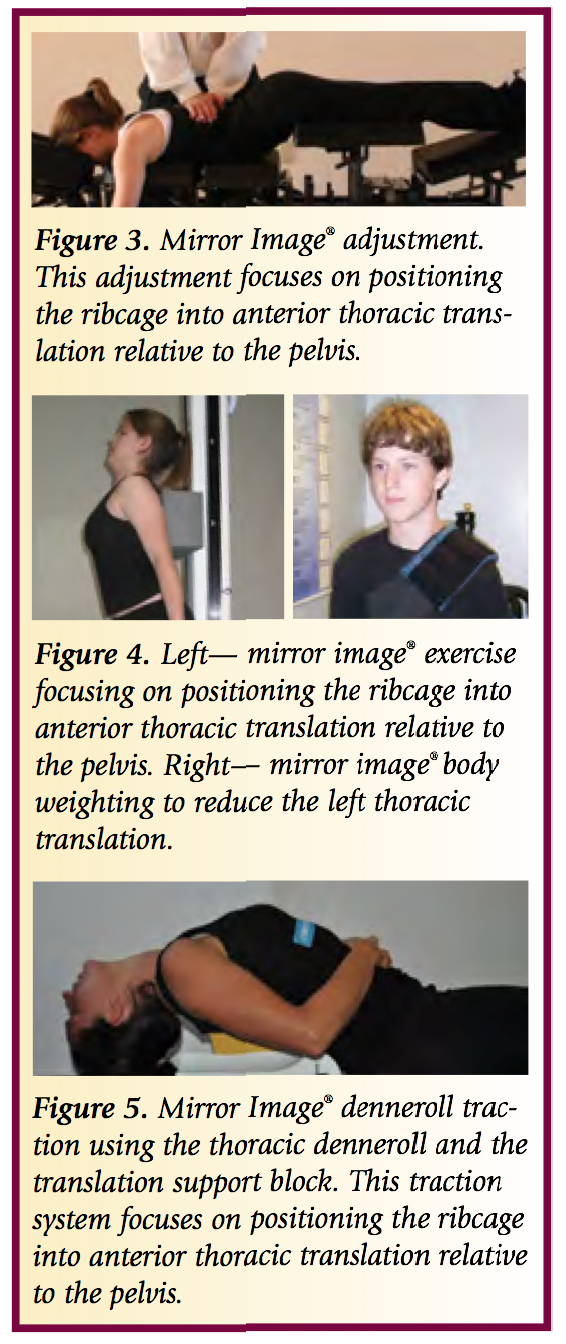

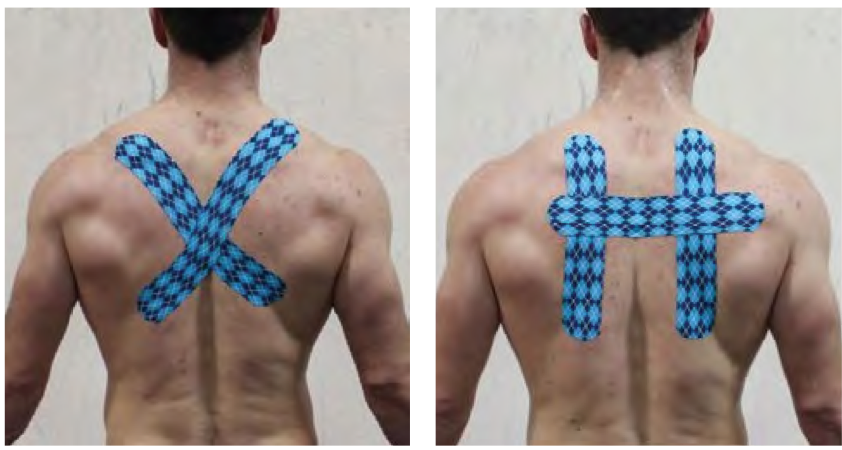

Care of the elderly patient is slightly different in the CBP setting as it requires a gentler; yet still patient centered approach. We are cautious not to use high-velocity manipulation with elderly patients and work primarily on improving their posture with gentle CBP Mirror Image adjustments. The CBP Mirror image exercises are incredibly important in increasing strength and stability of the core postural muscles. We recommend and use the PowerPlate® as this is an exceptional tool for the elderly to perform their Mirror Image exercises while getting maximal benefit from the whole body vibration or acceleration training.

The CBP Mirror Imag traction protocols must also be altered for the elderly patients, they must understand why we are using the traction and stressing the analogy that spinal change is a marathon and not a sprint is important to minimize injury. Most elderly patient in our office have radiculopathy, peripheral neuropathies, disc herniations and osteophytes so the use of distractive traction is often superior to compression traction which can irritate and worsen radiating symptoms.

Frequent re-evaluation and re-assessment of the elderly patient is possibly more important than any other age group. This is due to the fact that they often have significant health complications that ned to be assessed periodically. In our integrated setting it is easy for them to see our nurse practitioner or medical doctor if new symptoms arise, and for those of you who are not integrated, I would suggest having a close relationship with local providers to manage any health complications that may arise throughout care.

Diligent, patient, and compassionate care for the Elderly population can provide this segment with significant health gains, better posture and balance, less pain and a better overall quality of life. IF you would like more information on CBP care and the elderly, please attend any upcoming seminar.

Sample Patient Case:

Age: 87

Initial Complaints: Low back pain and left leg sciatic pain NRS 8/10

Oswestry: 58% disability. Significant depression due to worsening of pain, poor balance and coordination.

Patient was told by two other chiropractors they could not help her. She was told by a surgeon that she is not a candidate for surgery due to advanced age.

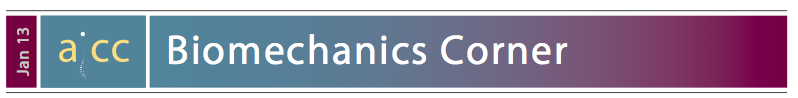

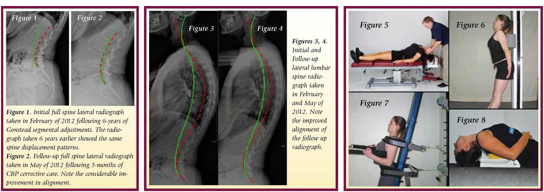

CBP Treatment: Mirror Image adjustments prone with the headpiece elevated and instrument adjustment to the spine. Mirror Image exercises; standing with a block in the lower thorax and head and ribcage retraction performed in-office and at home. Supine thoraco lumbar traction. Fulcrum of traction at thoraco-lumbar junction, 0° angle of pull and leg strapped below the femur heads, sustained for 12 minutes. Cervical Traction consisting of Pope-2-way type traction with a distractive force of 10 lbs and a finishing front weight of 18 lbs. sustained for 10 minutes.

Total treatments: 30 sessions

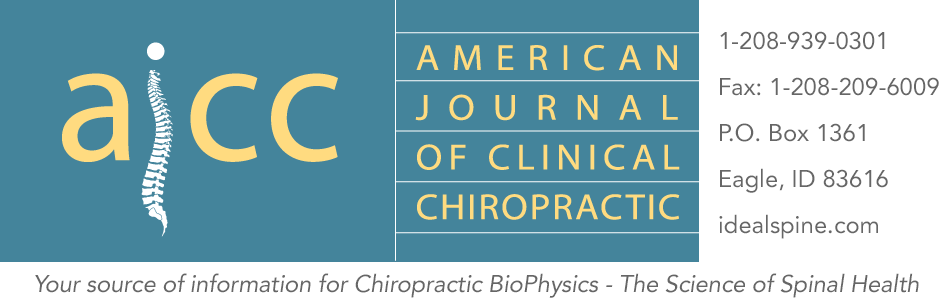

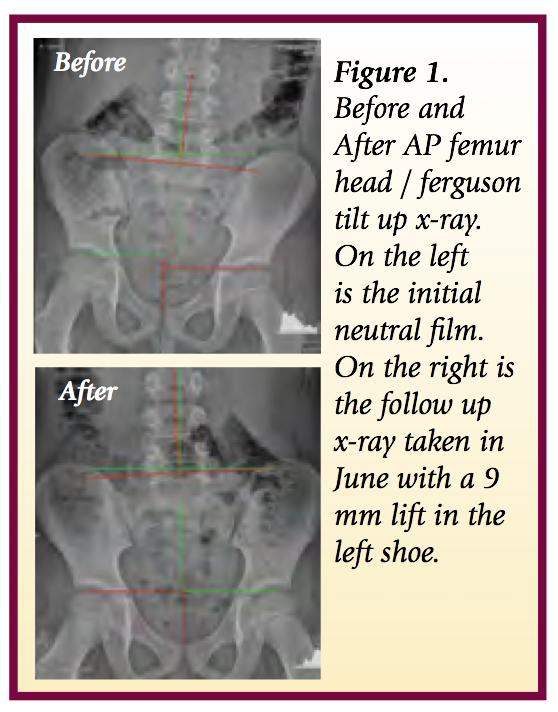

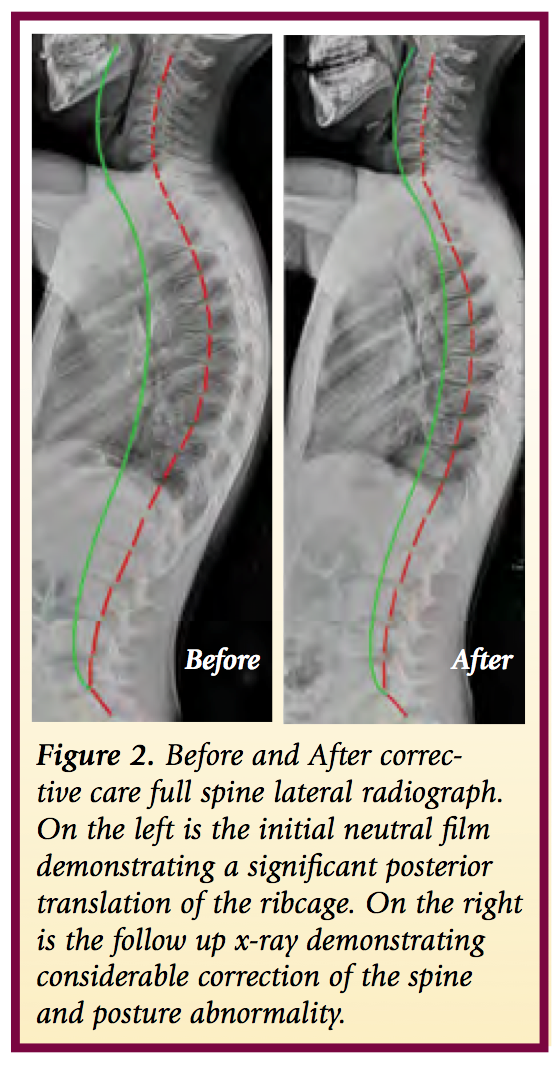

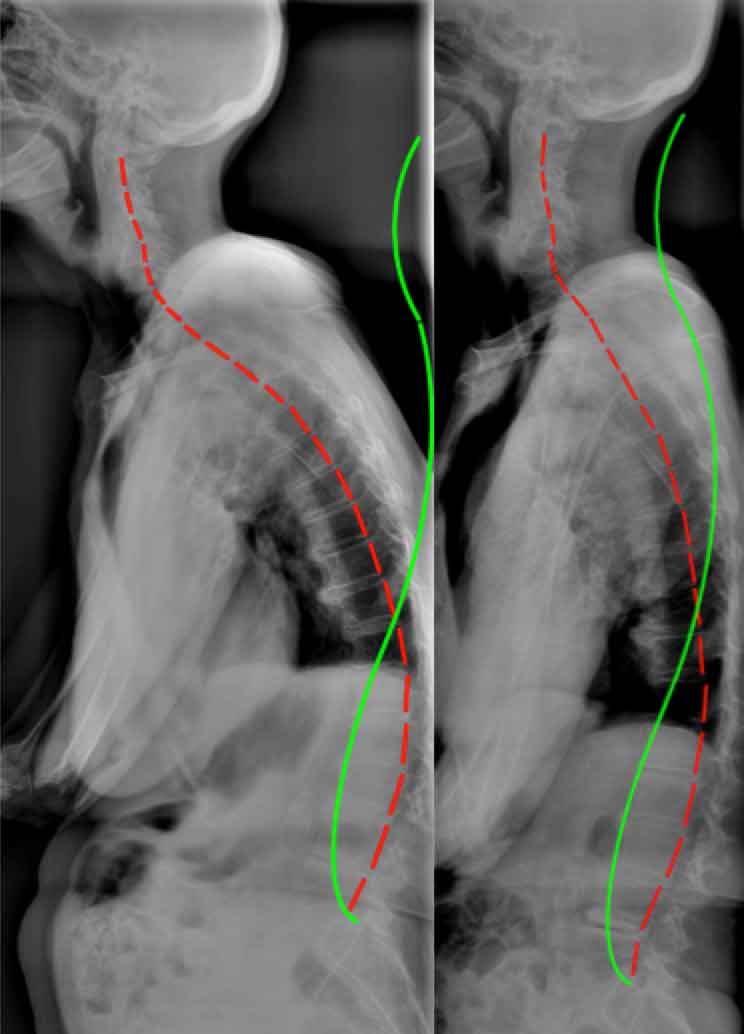

Figure 1. Before treatment and after treatment full spine radiographic changes due to CBP mirror image care over the course of 30 visits. Note that the follow up x-rays are taken a minimum of 3 days after the patients last treatment session. Thus, this is not an x-ray immediately after care. In this manner an accurate response to care can be found.

Figure 1. Before treatment and after treatment full spine radiographic changes due to CBP mirror image care over the course of 30 visits. Note that the follow up x-rays are taken a minimum of 3 days after the patients last treatment session. Thus, this is not an x-ray immediately after care. In this manner an accurate response to care can be found.

Final Complaints: Very rare low back pain (NRS2/10) Sciatica resolved, Depression significantly reduced and the patient states she feels better now than she has in decades. Oswestry: 8%.

Perspective on Patient Outcome:

It is my opinion that the improvement in the patient's condition, outcome measures, and self reported ability to function was due to the considerable improvement in the sagittal plane alignment of the patient's thoraco-lumbar curvatures and sagittal-forward balance. The references4-13 provided below provide evidence based support for this anecdotal but clinically obvious statement.

Reference Links

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25436061

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23307577

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25533322

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Kobayashi+T+Osteoporos+Int++2008

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11479757

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21198460

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24715607

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20480146

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Kamitami+2013

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12355123

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15972617

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19451575

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15450042

CBP Seminars | Comments Off |

CBP Seminars | Comments Off |  Chiropractic BioPhysics,

Chiropractic BioPhysics,  PostureRay

PostureRay